Imprisonment became a mass kind of punishment at the break of the 19th century and as Michel Foucault writes this was the beginning of the "humanitarian" penal system.1 The prison was to become "the punishment of civilized societies". Since then many concepts of an ideal prison have been put forward and the most famous of those is Bentham's Panopticon: a circular construction in the middle of which a sentry tower was supposed to be erected, ensuring constant control of the prisoners and the personnel although tangible presence of the wardens among the incarcerated could not actually be detected.

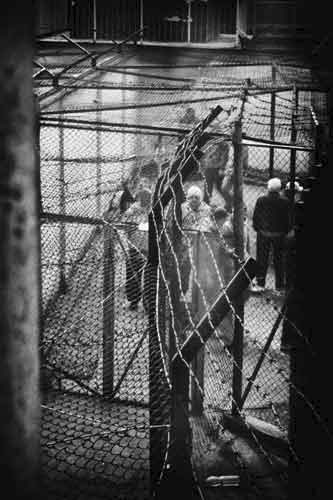

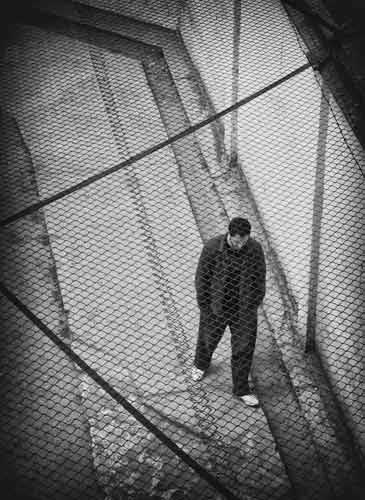

The penitentiary in which Agnieszka Prusak produced her Blow-up is one of the largest prisons in Poland and the people we see in her photographs are convicts with the highest sentences for most serious crimes. Those photographs are unique for various reasons, one of them being the fact that the prisoners agreed to show their faces.

Sociologists trying to pinpoint the reasons for abnormal and criminal behaviour have come up with many theories on the subject. Functionalistic answers interpret criminal actions as the result of structural tension between social groups that at the same time lack social mechanisms of moral regulations of behaviour. Theory of labeling by Howard Becker claims that regarding a given individual as a deviant - which can make him commit criminal acts - is not the result of the individual's behaviour but his way of talking, dressing etc. Becker said that deviant behaviour is the behaviour that people regard as such.2 The theory of conflict and new criminology describe criminality in terms of social structures, stressing the tendency of the ruling classes to retain their power.

The transformations of masculinity in contemporary culture have been discussed in many theoretical publications, also in Polish literature devoted to the subject. Analyzing this cultural phenomenon we encounter two main interpretative standpoints. Zbyszko Melosik describing the feminization of male identity and body as well as its medicalization (especially the medicalization of impotence and the pharmaceuticalization of happiness) speaks of the "crisis of masculinity". Other theoreticians propose an emancipatory hypothesis, stressing this aspect of the transformations which we observe that frees us from the stereotypes of "true masculinity".

The prison as a place which uses specific cultural codes influences almost every aspect of man's life (from language to his physical condition). As such it seems not to be a part of those emancipatory processes, so the crisis of masculinity apparently has not entered penitentiaries. Masculinity in prison functions as a transcendental habitus, the matrix of perception3 formed by the androcentric culture of the West. Agnieszka Prusak's photographs tell the story coming from a world ruled by the laws identical with those of the patriarchal Christian culture. As the author of Discipline and Punish argues, the prison reproduces the models of family, army, factory workshop, school and the court of law which are dominating at a given moment behind the walls of the jail. Along with those models it becomes the sanctuary of "true masculinity", the stronghold of masculinity of the macho type. As Foucault writes, the prison to a certain extent is an institution that resembles more severe barracks, a school without mercy or a darker factory, but ultimately all these places are not so different4. In this context the title of Prusak's exhibition, Blow-up, gains unexpected meaning. It not only refers to the famous film by Antonioni but also becomes the synonym of mechanisms which produce the figure of the "masculine criminal" - or the enlargement of the universally accepted traits of an individual to such proportions in which they are seen as deviant.

A prison imposing its rules on the prisoner creates "an ideal criminal", a dangerous man who symbolizes the inadaptability to live among the "normal" and "decent" citizens. Using the stereotypes which function among "free" men, prison brings to life a virtual Other who incorporates social fears and frustrations of the scapegoat.

Prusak's group photographs of prisoners confirm the idea that the prison and the criminal are very much alike. Moreover, the prison seems to be established in order to fulfill his identity, constituted as social essence and transformed into destiny5. Strong men who bravely stare into the camera lens, muscular guys, dressed in track suits and shoes, demonstrate their physical and psychological strength. They seem cynical and funny in a dangerous way. Dynamic frames of those photographs from the prison yard - the most voyeuristic of all - show the prisoners' ways of self-creation through the display of their fitness and physical stamina. The world of Prusak's reportage generates the energy of unspoken desperation, hidden under the accepted role of the "tough guy". The artist breaks the illusion of this "popular theatre" with her portraits/"monodramas" in which every character presents himself and his environment. The personality of each individual is completed by props and the pose he adopts - therefore among Prusak's characters we can find melancholics, amateur artists and even vacationers. If not for the context of the prison yard pictures in which we can see characteristic prison architecture, bars and sentry towers, the "criminal" identity of the models would become less obvious or even completely invisible.

Our fascination with the portraits of the prisoners, the fact that by means of those photographs we want to participate in their world even if from afar seems to be the result of our need of cognition, the need to know - because thanks to those people we can name, characterize and define Evil. What is paradoxical is the fact that identifying its enemy, society calls on the most important (from its point of view) "masculine" values like strength, courage, honour etc. Enlarged out of proportion these seem to symbolize the "powers of chaos" which threaten to violate the rules of social life.

The artist exhibits her portraits in a wooden container hand-made by one of the prisoners and called "the filing cabinet". Files or archives as the place where information is gathered is usually associated with complete depersonalization: people are replaced here by numbers, symbols or dry descriptions and characterizations. In this case the cliche has been inverted and "the filing cabinet" turns out to be the collection of the most intimate pictures of the series. However, we can feel the conflict between individuality and stereotype. These photographs still refer to the traditional model of masculinity in which femininity is reduced to an object, a sexual fetish (pornography in cells), while the work as a whole gains even religious validity (see the portrait of a prisoner holding his hand-made portrait of John Paul II).

Masculinity in the modern world became a fluid category which is gradually becoming harder and harder to grasp. What we call the crisis of masculinity, frustrating many disoriented men, may lead to criminal behaviour. From this perspective the prisoners change into victims as it turns out that masculinity conceived as the ability to reproduce, fight and perform acts of violence is in the first place a burden6. Pierre Bourdieu believes that some forms of courage, especially those that we can see in the behaviour of soldiers or policemen or even some criminal organizations, are the result of the fear of an individual who is afraid that he may lose respect or admiration of the given social group7. Bourdieu also stresses that what we call courage is very strongly entangled in cowardice because many murders, rapes, acts of abuse, maltreatment or other forms of domination are committed because of the typically masculine fear of being eliminated from the world of tough and fearless men8.

Agnieszka Prusak's black-and-white photographs are phenomenal. Their phenomenality is not based on any spectacular formal solution but on the fact that they reveal a living sphere of human activity which is normally not to be observed on a day-to-day basis, that functions according to its own rules and exists within a larger social structure.

Przemysław Chodań

2 See Giddens Anthony, Socjologia [Sociology], Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warsaw 2004, p. 231.

3 See Bourdieu Pierre, Męska dominacja [Male Domination], Oficyna Naukowa, Warsaw 2006.

4 Foucault Michel, op.cit., p. 225.

5 Foucault Michel, op.cit., p. 225.

6 Bourdieu Pierre, Male Domination, Oficyna Naukowa, Warsaw 2006, p. 64.

7 Ibidem, p. 66.

8 Ibidem, p. 66.

Copyright ©2010 Galeria FF ŁDK, Agnieszka Prusak, Przemysław Chodań