19 V - 9 VI 2000

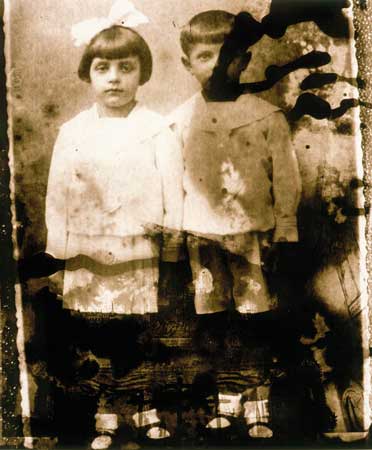

Fotografi z atrybutami, 1990

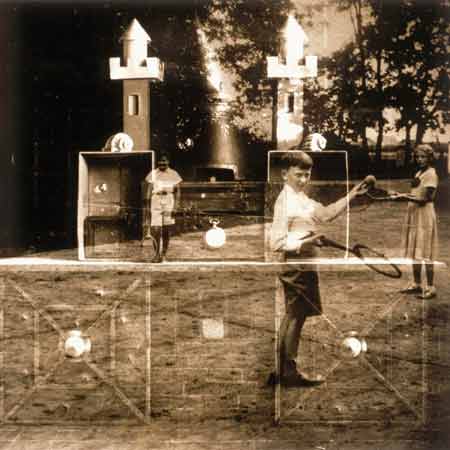

Zabawy dzieciêce, 1988

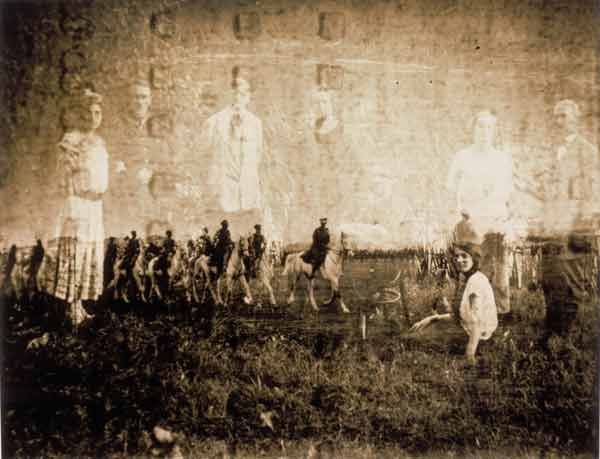

Ech wojenko, wojenko ... , 1987

Wojciech Prażmowski has been creating his pictures for many long years, consistently using to this end old photographs such as we all know from various family albums. Prażmowski gives new identity to anonymous characters from individual photographs, composing with their help paradoxical "new stories from the past". Using old photographs may be interpreted as an expression of the photographer's disbelief in photography's capability to preserve the image of the present moment and its impossibility to become an accurate account of the present. Perhaps because photography always shows the past, shows things that were "the present" when they were in front of the camera, but also things that inevitably become motionless images of the past at the moment when the shutter button of the camera is pressed. Snatching the moment away from the body of time, photography places the image once and for all in the past and in a way puts it to death along with everything that happened to be caught in the photograph. The hope that while preserving the image of the present one also prolongs its existence is probably illusory. "Oh, moment, stay!" - alas, photography is not able to answer that call. The duration of the moment is but a psychological impression. There is no present time in the world of matter which is subordinated to the laws of physics and towards which the camera lens is directed. Only those things which exist (i. e. which are beyond time), or those which used to be, are verifiable and measurable, while those things which will be may only be treated as a dubious hypothesis that might be realized or not when it will have passed into the past.

This relation between photography and time, its ultimate and irreversible attachment to time past, becomes the foundation of the game with the images of the past and the images of time that Prażmowski is playing in his work. The intensification of the existential experience of passing away, of which a photograph is the obvious proof, stimulates our emotions.

And these emotions are the reason that makes old pictures draw our attention to them. They force us to inspect the photographs closely even when the situations represented in them have no connection to our personal experience. Beside memory, photography seems to be the only effective ally in our struggle with the passing time. The ephemeral being of characters from Prażmowski's work has been recalled from the past solely thanks to photography and the will of the author. But contact with photography has also something paradoxical in it. Contact with old photographs helps us to distance ourselves from the past and allows us simultaneously to feel the present moment all the more intensely.

The melancholy connection with the past, established by Prażmowski's multi-layered works, is clear and it does not raise any doubts. The author stresses it both by means of form (the colour of the print, which is archaic sepia; positions and gestures of the models, characteristic for old photography), and by the contents of the pictures (historical costumes of the characters or the similarity of the situations presented in the pictures to various scenes known from other, older photographs).

The photo-montage technique of mixing various pictures together, employed by Prażmowski, serves well to render the nature of what the passage of time and the images from the past do to our memory. Time is the reason that makes the images from the past settle in our memory like debris on a reef. The images are folded over one another and sometimes they stick together. When looking only at their tiny particles, "the scraps of memory", the images of the past are not always easy to recognize. The task becomes more difficult as we go deeper into the lowest layers of those sediments. In Prażmowski's works the overlapping of the pictures not only makes each layer, folded over some other layer, create the illusion of spatiality, but it also makes the lower images look less and less legible. The viewer is forced by the power of his imagination to make the effort leading to the connection of all the images into one image and to the completion of what is otherwise fragmentary and illegible.

The nature of those pictures only partly resembles the mechanisms of our memory. It is also close to the poetics of dreams. Like in a dream, the time in the images is mixed up, the places are mixed up, but the contents of the vision is sufficiently expressive and clear, just like in a dream, when after awakening one is able to tell the dream in detail, but the time of those images and the dreamy visions is undetermined. All we know about it is that it passed, although we do not know when. We know that the situations in the images have to do with some "there" and "then", but we are unable to determine them in more precise terms. Thus the being of the characters presented in the photographs is suspended in some undetermined spatio-temporal relation, and the only thing which is certain about them is that they do not belong to our time. Quite often, in both kinds of pictures, physics and our everyday visual experience does not count at all. Such photographs are created independently of the rules of creating realistic imagery, free from the obligations imposed by the laws which must be obeyed in the real world.

The oniric aspect of Prażmowski's works has to do only with the mechanism of imagery, not with the images themselves. Dream images are the projections of our minds, sleeping and liberated from the slavery of rational thinking. Singular photographic images are objective and concrete. They form the material proof of the existence of real objects which they depict. This brings us close to poetic imagery, because here concrete elements are used to build free, non-literal and metaphorical contents. Perhaps the similarity to the mechanics of dream visions helps those internally complex, ambiguous pictures, which differ from everyday photography, to be read easier, because we are all used to the poetics of dreams.

Prażmowski's stories are fictions built from authentic photographs from the past. They are a kind of a fictionalized documentary, or perhaps a kind of a feature film based on authentic, although sometimes anonymous characters. But what is most important in them is not the plot or the story. The documentary character of a single photograph, confirming that what is shown in the photograph really existed or happened, is contrasted with the fiction created from single photographs of multi-layered pictures, both in the artist's "flat" works and in his photo-objects. This method allows Prażmowski to create an interesting and emotional tension in his works. It also allows the viewer to interpret those works much more freely than in the case of a single photograph, because they cause his imagination to work more intensely. Those stories ultimately take shape in the imagination of the viewer. The image here is only a cluster of visual suggestions - each of them may cause us to read the plot differently or to construct freely their internal narration. The interpretation of those pictures may be ambiguous, while their content is not given once and for all, which is not usually the case as far as many other photographs are concerned. Such freedom in the reading of any common, single picture, even when it is constructed in the most artificial way, is not normally allowed due to the nature of the essence of the very medium of photography.

The mechanism of the photo-montage image liberates the author from the limitations of documentary photography, and the viewer from the necessity of rational verification of what he sees. They both must reach into their imagination much deeper than in the case of normal photography. Simple identification of individual elements is not enough to give them some common meaning and form some kind of content.

It is only the unifying effort of the imagination, and not of the mind, that makes each of us construct some kind of content in our own way.

Time and its passing away, present so intensely in Prażmowski's works, are not indifferent for the characters-phantoms of the past, shown in his pictures, but also for us, the people who look at them. This is where the essential, universal aspect of the message hidden in the works by Prażmowski may be found. Even though those people and situations are not a part of our personal history, their entanglement in time and in distant events is not unusual as far as we are concerned. Whatever happened to them, which may be deduced from the presented stories - even if they are fictional - concerns also us, our personal experience or our emotional participation in the experiences of those phantoms of the past. In reality we do not differ much from them. Not counting the different historical costume, our experiences and their experiences, as well as the emotions accompanying them, are quite similar. When reconstructing their history we always make use of our personal experience because we know nothing of their experiences and biography. In a certain sense they are also our stories in which strange characters appear, because we involuntarily give them our own experiences and emotions in order to be able to read the story which the author only subtly suggests. That is why we must become at least partly engaged in what we read, see or would like to see, and actually nothing limits us in this instance. The degree to which we are engaged and the freedom of our interpretation are completely different in this situation than in the case of a single, normal picture. The viewer, to the given measure of his own sensitiveness and experience, becomes the co-author of these stories.

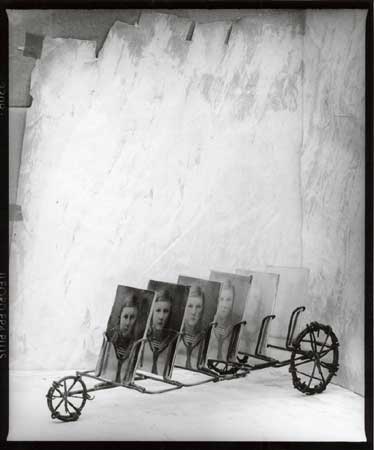

Prażmowski's independence in the face of reality, his independence as the author of pictures based on photography, gets deeper even more in his three-dimensional objects, made up of photographs or created for the purpose of taking photographs. In the first case Prażmowski creates real objects out of old photographs which are put together to form packages. Beside the situations described above, which refer to the contents, they also reveal an internal relation between photography as a flat image and a photograph which constitutes a spatial object.

In the case of objects made for the purpose of using them in photography Prażmowski yet again takes on the part of an artist directly involved in taking photographs, but he does not turn to external reality at all. In his series called "Tribute to/ Hommage a...", created in 1995, he creates specific reality solely for the purpose of photography, constructing objects which are supposed to symbolize a famous person. That is how a surprising evolution took place, an evolution whose main area was still photography. It developed starting from the image towards the object, and then back from the object to the image, without referring once directly to external reality or some concrete "here and now".

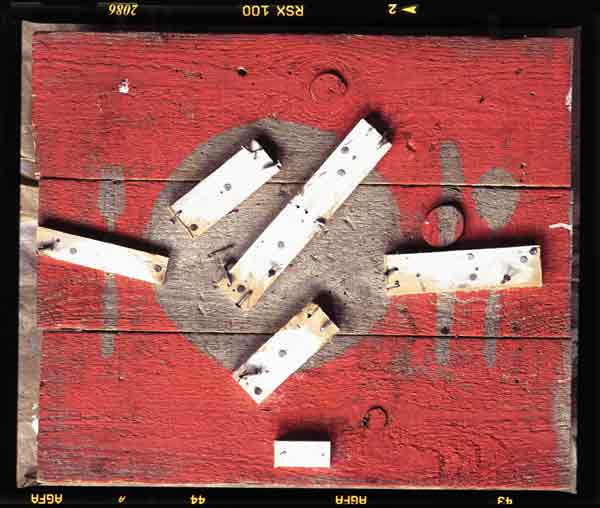

However, the latest works by Wojciech Prażmowski seem to point to the change in his attitude towards photography and external reality. His series, created in 1999, called "White, Red and Black" is probably one of the signs of his return to the present. The author shows in those works manifestations of white, red and black ideologies and their visual imponderables which the artist has found in contemporary Polish iconosphere.

So the return to the real world is radical, both in the contents and form of those works. The old convention of photo-montage was replaced by the convention which comes close to documentary, and even journalistic photography. The old universal content, referring to the existence of anonymous characters from undetermined past was in turn replaced by journalistic content which has to do with the current political debates on the subject of the place and the mutual relations between ideological traditions, symbolized by the colours forming the title of the series.

Prażmowski's poetics has also changed radically. In his pictures based on old photographs the freedom of creating meanings was shared by both the artist and the viewer. Guided by intuition and imagination they were both able to shape the contents freely. But in the case of his last series of works the freedom of the artist and the viewer is limited. The author follows those elements in reality which may be found in the title, while the viewer must find in the pictures the very same contents the author has found in them. The picture becomes a riddle/puzzle whose solution may be one answer only, and the key to the solution is the title.

Perhaps the direct contact with reality and photographying its current manifestations which are, admittedly, also entangled in history and shown without any manipulations within the image, marks Prażmowski's return to the faith in a single photograph which might be able to preserve the image of the present moment and become a form of a testimony of the present time. But what may be also seen in those works is a dramatic gesture of a photographer who wants to preserve the identity of his profession, seriously threatened by the evolution described above.

But can the turn towards events taking place here and now allow Prażmowski to remain equally free and independent as he used to be when working with images of the undoubtedly historical past?

Lech Lechowicz, April, 2000

translated by Maciej Ĥwierkocki

Zapominanie, 1996 (photo-object)

Tribute to A. Hitchock, 1995

Stó³ bia³o-czerwony, 1997

Stó³ wielkanocny, 1997

Fototapeta: Wojciech Prażmowski

Copyright ©2000 Wojciech Prażmowski, Lech Lechowicz, Galeria FF £DK