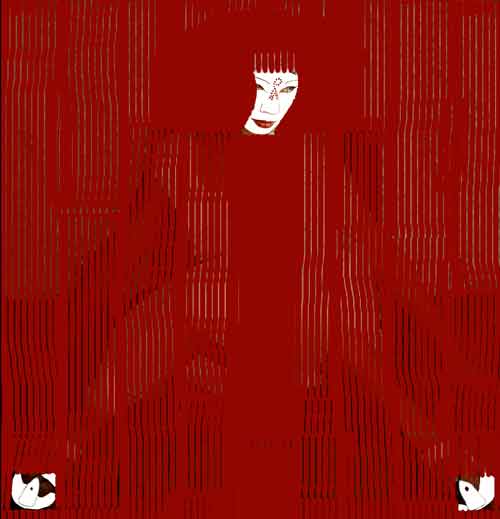

from the series Dolls

from the series Dolls

Night is the Mistress of Dreams who endows us with mysterious experiences of imagination. She writes irrational stories which are amazing because the sensations they cause are never obvious and even to the people who dream them they seem to be some kind of caballistic charades. Among the fragments of images, symbols and impressions, difficult to define unambiguously, our true image is revealed. In the darkness of the night, under our closed eyelids, puffy with sleep, a truly "naked" man is born. His nakedness symbolizes vulnerability and the impossibility of hiding even the most shameful aspects of our psychological construction. All our fears, frustrations, long gone but uncured memories and smothered energies enter the dominion of Morpheus. Sleep not always brings peace and carries us away to idyllic, mental Arcadia. More often dreams are rather like a garbage dump of our subconsciousness, a battlefield in which our Ego, rooted and entangled in reality, struggles with the Ego which is a primal voice, free from all kinds of everyday restrictions, a scream of passion. This voice, resounding in the darkness of the night, belongs to Tess...

Indeed, Irena Walczak's photographs are such dreams registered consciously, within the waking world, recorded on light-sensitive paper. These extremely personal works are woven from material which makes up an extremely rich sensibility of the artist, material which is at the same time carefully isolated from the external world. Looking at the series called Dreams for Tess, which is also the title of the whole exhibition, we are struck by a heavy load of psychological exhibitionism as well as by the accompanying fear of revealing too much of oneself, the fear of telling us too many painful secrets from the soul's very bottom. The photographs show faces of enormous eyes, open wide with fear, and open mouths, prepared to break the dead silence. They are apparently ready to go, overflowing with the excess of smothered feelings, but still motionless, as if paralyzed by the overwhelming power of what they would like to verbalize. I should rather say that they are more like suggestions of images than veristically rendered human portraits.They seem transitory as dreamy holograms whose psychodelic message is still overpowering. They come from the darkness of the nightmare of which they are a part. In one photograph they are crowded together, shown at the moment of eruption and multiplied, and therefore they intensify the feeling of horror. In other photographs they appear alone and attract our attention by the persistence and directness of their gaze. One particular technique which stresses their dramatism and spectral character is the contrastive lighting of the faces which imitates candlelight.

The second group of the pictures in the series is made up of images of no less unreal figures, made of some undefined substance which goes beyond literal corporality. After all, immaterial, dreamy hallucinations are not copies of shapes objectively existing in reality and they do not allow the artist to give her models tissue, bones or muscles. Irena Walczak constructs her fantastic people from simple, decorative elements, drawn from the artistic repository of Gustav Klimt: sparkling spirals, rings and carefully woven nets. The faces, however, retain a specific kind of realism because the expression of depth which interests the authoress the most is visible in them. In the case of these photographs deformation and "disembodiment" do not serve to build the atmosphere of tension or fear, or at least this is not their basic aim. They are more of a projection of interests and dreams - visions which have come into being as the result of observation of everyday life, filtered through the metaphors of dreams.

The oneiric world of Irena Walczak is also inhabited by other creatures. Judging by their bodies and dress one might suspect that they are women. Their faces are hidden under exotic, white Japanese masks which make it almost completely impossible to distinguish them. They just stand there, indifferent and removed. They adopt attractive poses and their tight dresses cling to their shapely bodies but they deny us the right to see their faces. Aesthetic precision, sleekness and masks make their human attributes disappear under these additional, beautifying superstructures. They are artificial and de-humanized, like the purple crust scabbed over their heads. The artist calls them Dolls. The feeling of alienation and marionette-like paralysis is intensified even more because Walczak deconstructs the physical integrity of her Dolls. She often breaks down their bodies and faces into fragments and divides them into little modules. Contrary to Hans Bellmer's deconstruction of girlish toys, the Polish artist does not completely severe individual parts of their anatomy from the torso. She rather adopts a method which resembles pointilism in painting - so the seemingly separated elements of her composition come together in the eye of the beholder, creating a solid structure.

Irena Walczak's photographs, especially from the Dolls series, bring to mind the name of Aubrey Beardsley, an artist distant from Walczak in time but close to her works in terms of the idea standing behind them. What is it that links the Polish photographer of the 21st century, who uses the latest electronic techniques, with the English graphic artist, living at the end of the 19th century? Both made or make use of their interest in gloomy, depressing and disheartening subjects, connected with the exploration of human nature. Walczak manifests this concern through the poetics of dreams, present in her photographs, the revelation of anxiety and the dark aspects of the human mind. However, she transforms her personal experiences and reflections into raw material which serves as the source of her artistic inspirations. In this context her behaviour is quite spontaneous and natural. Aesthetization appears in her works as the means to an end, not as an end in itself. Whereas in the case of a classic artist like Beardsley, not counting the sacralization of evil and ugliness, we have to do with the creation of specific aesthetics au rebours, with an exclusive cult of artificiality and the degradation of naturalness. Looking at the most famous graphic works of Oscar Wilde's friend we cannot help detecting especially their stylistic resemblance to the photographs of the young Polish artist. His lofty femmes fatales like Salome, drawn in fine lines and bathing in black and white, resemble the graphic structure and distance emanating from Walczak's masked Dolls. Reading what Arthur Symons has to say about Beardsley's women we can treat his words as comments on the Masked Creatures of Irena Walczak: "They possess spiritual and bodily sensibility which dresses them in paleness and makes them exist in blissful reverie. They are too deeply entranced to be really natural, to fully become either bodies or spirits.".1 The only elements in Dolls which are vigorous and searing with curiosity of the world are their penetrating eyes. They allow us to see in those dressed-up mannequins a man, a woman or a child - a creature which, in spite of everything, has feelings. We cannot be absolutely sure who is hiding under the mask but through the holes cut out in them someone is looking at us, someone who denies the apparent lifelessness of the Dolls but who perhaps is not ready to or who is afraid to cast away their "facial" armour. In Japan geisha's white-painted face, contrasting with her shironuri make-up, was meant to be seducing and encouraged men to take part in the social game, but it also provoked questions about what was hiding beyond the abyssal gaze of a woman's almond eyes. Irena Walczak's dolls tempt us with their gazes and encourage to take up a similar challenge: "In these lustful eyes we can always see spiritual, not only bodily insatiability (.)".2

One feature that defines the original style of the artist in question is the link between her deep emotionality and decadence, and something that is visible in many of her works, namely the inclination to subordinate her compositions to precise axial systems and the care we can see in the painstaking work she takes to complete the aesthetic aspect of her photographs. We can notice this especially in small format photographs presented at the FF Gallery. Many of them contain motifs known from Dolls, but they are multiplied and overgrown on the plane like exotic and sensual flowers. Multiplying particular elements and shapes Walczak achieves unusual but moderate painting effects so as not to irritate the viewer with baroque splendour. Her works are saturated with the atmosphere of the Far East. Dolls already contained allusions to Japanese art, especially because they made use of the motif of the mask. They were also formally associated with the traditional speciality of Japanese culture - wood engraving. The artist also materializes her visions employing techniques used by the authors of Buddhist or Hindu paintings and sculptures, techniques that we can see in detailed ornaments and the open-work of given compositions. Some of her photographs are composed within the plane of a circle. One photograph is full of plastic designs framed by faces seen in profile and brings to mind the structure of a chakhra or mandala. In Dolls masked women are holding large rings, and in sanscrit an arch or a circle means "mandala" which in Eastern philosophy is like a diagram of the traces of the presence of God on Earth. It is an order-imposing synthesis of the movement of beings which move gradually from chaos to harmony because it links the opposite spheres of heaven and earth. However, it is also a reproduction of the state of mind of whoever is drawing it. It tells us of the levels of consciousness inaccessible even to the author.

Irena Walczak draws her own "photographic mandalas" in a similar way, mandalas in which psychological and emotional decadence co-exists with the order of symmetrical systems and technical perfection. The authoress also tell her own intimate stories through those photographs. She hides her psychological nakedness in encoded symbols which may be difficult to decode even for her: in horrifying mouths, unable to scream, in women-dolls or in a girl of phosphorescent green eyes dressed in a dress that Velasquez's infants used to wear.

The exhibition entitled Dreams for Tess, presented at the FF Gallery, is actually Irena Walczak's debut. Her youthful works, however, seem artistically mature, both from the point of view of their rich contents and the artist's technical ability. Walczak, who takes her photographs in an analogue way and then transforms them by means of a computer programme, violates the conventional fashion in which we perceive photography. Using a computer she broadens her creative horizons and creates her original style. Her unique technique erases the boundaries between traditional photography and graphic art. She is an heiress of the thought of symbolists and surrealists, inclined towards the poetics of Tomasz Sikora and Erwin Olaf, but remains untouched by any forms of deeper infiltration of specific tendencies or artistic fads. She realizes her own, unique creative ideas. She is dreaming for Tess.

Indeed, Irena Walczak's photographs are such dreams registered consciously, within the waking world, recorded on light-sensitive paper. These extremely personal works are woven from material which makes up an extremely rich sensibility of the artist, material which is at the same time carefully isolated from the external world. Looking at the series called Dreams for Tess, which is also the title of the whole exhibition, we are struck by a heavy load of psychological exhibitionism as well as by the accompanying fear of revealing too much of oneself, the fear of telling us too many painful secrets from the soul's very bottom. The photographs show faces of enormous eyes, open wide with fear, and open mouths, prepared to break the dead silence. They are apparently ready to go, overflowing with the excess of smothered feelings, but still motionless, as if paralyzed by the overwhelming power of what they would like to verbalize. I should rather say that they are more like suggestions of images than veristically rendered human portraits.They seem transitory as dreamy holograms whose psychodelic message is still overpowering. They come from the darkness of the nightmare of which they are a part. In one photograph they are crowded together, shown at the moment of eruption and multiplied, and therefore they intensify the feeling of horror. In other photographs they appear alone and attract our attention by the persistence and directness of their gaze. One particular technique which stresses their dramatism and spectral character is the contrastive lighting of the faces which imitates candlelight.

The second group of the pictures in the series is made up of images of no less unreal figures, made of some undefined substance which goes beyond literal corporality. After all, immaterial, dreamy hallucinations are not copies of shapes objectively existing in reality and they do not allow the artist to give her models tissue, bones or muscles. Irena Walczak constructs her fantastic people from simple, decorative elements, drawn from the artistic repository of Gustav Klimt: sparkling spirals, rings and carefully woven nets. The faces, however, retain a specific kind of realism because the expression of depth which interests the authoress the most is visible in them. In the case of these photographs deformation and "disembodiment" do not serve to build the atmosphere of tension or fear, or at least this is not their basic aim. They are more of a projection of interests and dreams - visions which have come into being as the result of observation of everyday life, filtered through the metaphors of dreams.

The oneiric world of Irena Walczak is also inhabited by other creatures. Judging by their bodies and dress one might suspect that they are women. Their faces are hidden under exotic, white Japanese masks which make it almost completely impossible to distinguish them. They just stand there, indifferent and removed. They adopt attractive poses and their tight dresses cling to their shapely bodies but they deny us the right to see their faces. Aesthetic precision, sleekness and masks make their human attributes disappear under these additional, beautifying superstructures. They are artificial and de-humanized, like the purple crust scabbed over their heads. The artist calls them Dolls. The feeling of alienation and marionette-like paralysis is intensified even more because Walczak deconstructs the physical integrity of her Dolls. She often breaks down their bodies and faces into fragments and divides them into little modules. Contrary to Hans Bellmer's deconstruction of girlish toys, the Polish artist does not completely severe individual parts of their anatomy from the torso. She rather adopts a method which resembles pointilism in painting - so the seemingly separated elements of her composition come together in the eye of the beholder, creating a solid structure.

Irena Walczak's photographs, especially from the Dolls series, bring to mind the name of Aubrey Beardsley, an artist distant from Walczak in time but close to her works in terms of the idea standing behind them. What is it that links the Polish photographer of the 21st century, who uses the latest electronic techniques, with the English graphic artist, living at the end of the 19th century? Both made or make use of their interest in gloomy, depressing and disheartening subjects, connected with the exploration of human nature. Walczak manifests this concern through the poetics of dreams, present in her photographs, the revelation of anxiety and the dark aspects of the human mind. However, she transforms her personal experiences and reflections into raw material which serves as the source of her artistic inspirations. In this context her behaviour is quite spontaneous and natural. Aesthetization appears in her works as the means to an end, not as an end in itself. Whereas in the case of a classic artist like Beardsley, not counting the sacralization of evil and ugliness, we have to do with the creation of specific aesthetics au rebours, with an exclusive cult of artificiality and the degradation of naturalness. Looking at the most famous graphic works of Oscar Wilde's friend we cannot help detecting especially their stylistic resemblance to the photographs of the young Polish artist. His lofty femmes fatales like Salome, drawn in fine lines and bathing in black and white, resemble the graphic structure and distance emanating from Walczak's masked Dolls. Reading what Arthur Symons has to say about Beardsley's women we can treat his words as comments on the Masked Creatures of Irena Walczak: "They possess spiritual and bodily sensibility which dresses them in paleness and makes them exist in blissful reverie. They are too deeply entranced to be really natural, to fully become either bodies or spirits.".1 The only elements in Dolls which are vigorous and searing with curiosity of the world are their penetrating eyes. They allow us to see in those dressed-up mannequins a man, a woman or a child - a creature which, in spite of everything, has feelings. We cannot be absolutely sure who is hiding under the mask but through the holes cut out in them someone is looking at us, someone who denies the apparent lifelessness of the Dolls but who perhaps is not ready to or who is afraid to cast away their "facial" armour. In Japan geisha's white-painted face, contrasting with her shironuri make-up, was meant to be seducing and encouraged men to take part in the social game, but it also provoked questions about what was hiding beyond the abyssal gaze of a woman's almond eyes. Irena Walczak's dolls tempt us with their gazes and encourage to take up a similar challenge: "In these lustful eyes we can always see spiritual, not only bodily insatiability (.)".2

One feature that defines the original style of the artist in question is the link between her deep emotionality and decadence, and something that is visible in many of her works, namely the inclination to subordinate her compositions to precise axial systems and the care we can see in the painstaking work she takes to complete the aesthetic aspect of her photographs. We can notice this especially in small format photographs presented at the FF Gallery. Many of them contain motifs known from Dolls, but they are multiplied and overgrown on the plane like exotic and sensual flowers. Multiplying particular elements and shapes Walczak achieves unusual but moderate painting effects so as not to irritate the viewer with baroque splendour. Her works are saturated with the atmosphere of the Far East. Dolls already contained allusions to Japanese art, especially because they made use of the motif of the mask. They were also formally associated with the traditional speciality of Japanese culture - wood engraving. The artist also materializes her visions employing techniques used by the authors of Buddhist or Hindu paintings and sculptures, techniques that we can see in detailed ornaments and the open-work of given compositions. Some of her photographs are composed within the plane of a circle. One photograph is full of plastic designs framed by faces seen in profile and brings to mind the structure of a chakhra or mandala. In Dolls masked women are holding large rings, and in sanscrit an arch or a circle means "mandala" which in Eastern philosophy is like a diagram of the traces of the presence of God on Earth. It is an order-imposing synthesis of the movement of beings which move gradually from chaos to harmony because it links the opposite spheres of heaven and earth. However, it is also a reproduction of the state of mind of whoever is drawing it. It tells us of the levels of consciousness inaccessible even to the author.

Irena Walczak draws her own "photographic mandalas" in a similar way, mandalas in which psychological and emotional decadence co-exists with the order of symmetrical systems and technical perfection. The authoress also tell her own intimate stories through those photographs. She hides her psychological nakedness in encoded symbols which may be difficult to decode even for her: in horrifying mouths, unable to scream, in women-dolls or in a girl of phosphorescent green eyes dressed in a dress that Velasquez's infants used to wear.

The exhibition entitled Dreams for Tess, presented at the FF Gallery, is actually Irena Walczak's debut. Her youthful works, however, seem artistically mature, both from the point of view of their rich contents and the artist's technical ability. Walczak, who takes her photographs in an analogue way and then transforms them by means of a computer programme, violates the conventional fashion in which we perceive photography. Using a computer she broadens her creative horizons and creates her original style. Her unique technique erases the boundaries between traditional photography and graphic art. She is an heiress of the thought of symbolists and surrealists, inclined towards the poetics of Tomasz Sikora and Erwin Olaf, but remains untouched by any forms of deeper infiltration of specific tendencies or artistic fads. She realizes her own, unique creative ideas. She is dreaming for Tess.

Eva Milczarek

translation by Maciej ¦wierkocki

translation by Maciej ¦wierkocki

1 Arthur Symons, "Ver Sacrum", 1903

2 Op. cit.

from the series Dreams for Tess

from the series Dreams for Tess

Illustration No titles

Illustration No titles

Illustration No titles

Exhibition organized as part of an

OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME

"Art Promotion"

Copyright ©2006 Galeria FF £DK, Irena Walczak, Eva Milczarek.