colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

City as a Palimpsest, City of Destruction

£ód¼, especially its major "industrial" part, is a unique place as far as I am concerned. As a student I often visited and watched this city and at that time I always felt its uniqueness, its extraordinary aura and a specific kind of oscillation: impossible-possible. Each time I used to find in it some kind of unreality which probably originates from the confrontation, combination or even collision of what used to be and what is now; of the old and the new, the reasonable and the absurd, the comprehensible and the incomprehensible. Every city is built of many layers and history always leaves its traces in it, traces whose scale and resilience is changeable and revealing. £ód¼ is exceptional for me because of the uncanny jumble of all those elements and because contrary to the destructive activity of time and people, those signs, even the tiniest of them, still remain visible. Together they form a space which - even though created by man - seems to possess an independent existence (.) 1.

Rados³aw Wojnar's photographs from the series £ód¼ Fabryczna [Industrial £ód¼] are a portrait of the city. They are a record of the lonely rambles of the author through the streets of £ód¼, gnawed by the worm of destruction. However, saying that those works are but a registration or an objectivization of reality would be quite a misunderstanding and an error. They are rather attempts at registering a certain feeling - an impression that reaches beyond the superficially documentary character of the images and exists on the border between the activitiy of Time, Man and Place.

The city conceived as a modernist metropolis fascinated even the French Impressionists who in the Parisian boulevards at the break of the 20 th century saw the seeds of the future dynamic technological and industrial revolution. The Italian Futurists made the city an object of a literally obsessive civilizational worship. Fritz Lang's famous film Metropolis and Aldous Huxley's novel "Brave New World", though anti-utopian, preserved, after all, the image of the city as a perfectly designed (from the engineering point of view) urban structure, able to meet the expectations of modern man - the man of the era of progress, proud of his mental powers. In this perspective the city seems a self-sustained structure - it is an independent entity, in spite of the fact that created by a human hand, because it is detached and separated from man by the industrial tissue which is not a product of Nature. We have to do here with the movement in the opposite direction from the one suggested by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: it is an escape from elemental Nature into orderly Urban Culture. This "romantic" myth of the city contains, however, a double paradox - because although the city usurps the right to autonomous existence, it was created by man and established by him, and because although it is an artificial creation which transforms the environment of animals and plants, it is also at the same time the product of the activity of man who is himself one of the materializations of Nature and biology, i.e. of the organic world. The city, stigmatized by Time on top of that, becomes the sphere of the struggle of those extreme powers which model its specific character and individual appearance.

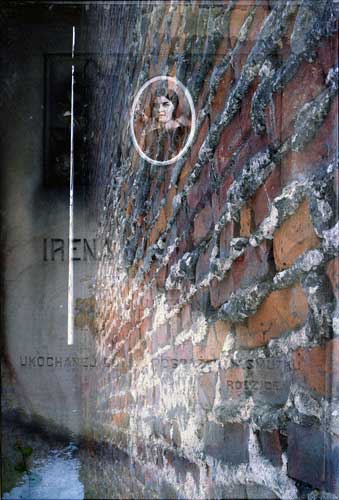

£ód¼ seen through the photographic eyes of Rados³aw Wojnar is precisely such a sphere where different, incompatible elements intermingle. On the one hand the city intrigues and attracts, while on the other it overwhelms and frightens him. The author finds living history written on its walls, in its backstreets and tenement houses - he sees continuity which links the past with the present. £ód¼ is a city permeated by the atmosphere of mysteriousness which not quite comprehensibly peeks through the banality and mediocrity of its grey landscape of ruined houses, dilapidated walls and shattered glass in the windows of local factories. The artist visited all nooks and corners of £ód¼, photographying, among others, streets like Piotrkowska, Sienkiewicza and Wschodnia, as well as motifs known from the cemetery in Ogrodowa street. However, these photographs do not literally and completely represent given places or objects, as Wojnar often shows us just a fragment or a small detail of reality which lose touch with the rest of the familiar urban landscape precisely because of their fragmentariness. He is more interested in probing the structure of the matter or relations between shapes and texture than in faithful representation of the landscape of £ód¼ that would resemblie a picture postcard. This is why the motifs Wojnar photographs (like the tectonics of the walls, decrepit plaster-work, decorative patterns of the floors, vivid graffiti lines and twisted pipes) gradually become less and less mimetic and enter the territory of abstract imagery. Like in the case of his earlier series: Faces in Wood, The Touch of Space or Now, the starting point of Wojnar's creative search becomes a given object-detail (a piece of wood; elements of the natural world - like sand, a sea-wave, or parts of the body, like a hand - or the word "now", meaning its graphic representation, written on a piece of paper), which is later transformed by the artist in time and space and dematerialized to carry a different, not only physical message.

The absurdity of the Industrial City, captured on film by the artist from Warsaw, recalls Lautréamont's example - found in one of his texts - of the meeting of a sewing machine with an umbrella on a dissecting table. In normal conditions such objects would never be assembled together. But from the point of view of surrealism only such a meeting of apparently mismatched elements of reality makes up its real image as it goes beyond its everyday appearance. Similarly, the old Textile City is somewhat surrealistic, because its landscape is full of contrasts. Scheibler's, Grohman's or Poznański's textile plants, eclectic staircases, 19 th century architectural details that in gradually weakening voices speak about their past glory, stand next to dilapidated gateways, among vulgar writings on the walls and surrounded by rowdy graffiti from a different era. Our shock is the result of the meeting of those asymmetric worlds in the huge urban area - the meeting of the old and the new, of what is still beautiful with its passing beauty and what already is extremely ugly with the ugliness of today. Those factors affect the seemingly unreal yet perceptible situation in which we face something that is Impossible, but nevertheless Exists - the Surreal City.

£ód¼ in Wojnar's interpretation is an urban palimpsest through which different layers of time can be seen and that is why infinitely many "histories" have been carved out on its surface. Time exercises its destructive, totalitarian power over the architecture of £ód¼ and the boundless human wave, rolling every day through its industrial organism, and it intensifies its slow agony. £ód¼ is dying, overgrown by the cancer cells of the activity of Time and Man, and the measured passing of each moment marks the road towards its destruction. The tangible evidence of this destruction and its bloody harvest are the teeth of Time which regularly tear out pieces of the meat of the city. Rados³aw Wojnar photographs places killed by Time and stigmatized by obliteration which fall apart and into the most sordid of ruins. He shows a fallen, mistreated £ód¼ which becomes a specific memento mori, a symbol of vanitas. - but he never shows people. He is trying to present the city as a sovereign structure, an object, not the subject of his photographs, although this impression does not dominate over the images. Nevertheless we feel human presence in this city. Even though man is not physically depicted in the pictures, he marks his presence in them by means of a suggestion, an allusion or the surrogate of his carnality - like the oval tombstone photograph of a woman or advertising posters with pictures of models. The space of the city conceived as a singular entity, independent of human Existence (views of empty walls, stairs, factories and tenements), mingles with the space that still remains man's domain. People leave their traces on the city's body and therefore have some bearing on its specific atmosphere (as the city is also the sum of all individual human acts). They live enclosed among the objects which belong to them and which can be seen in the photographs, like a car, garbage cans, the washing on a clothes-line or the names of tenants on the intercom. Such objects "people" the seemingly empty space anew. It is in £ód¼ that I often recall what Franciszek Starowieyski once said - that "Man is but an episode in the life of objects" 2 - says Wojnar, quoting a well-known painter. One of the things that clearly sanction human existence in the city is writing - especially in the form of vulgar slogans written by football fans. That is why Wojnar's pictures gain an additional dramatic aspect and dynamic character. A similar idea lies behind the author's frequent usage of graffiti as a motif which is a form of individual expression, projected onto "the skin" of the city. Moreover, graffiti possesses a value indispensable for any artist, namely the value of an ornament which becomes a vital element of creation in the composition of some photographs. Spontaneous graffiti lines, so affectionately photographed by the author, bring to mind the mood of Taschist painting, followed in the 1950s by Georges Mathieu or Tadeusz Kantor.

An equally important aspect of these works is the truth of the photographed object merging with the role of memory that preserves images. Photography for Rados³aw Wojnar is the evidence of some reality that came into being in front of his camera and is real in the sense that the image reproduces what his eyes saw at the moment of its registration. This does not mean that Wojnar concentrates only on the documentary aspect of photography. On the contrary, as he himself says, he has always found "pure" photography unsatisfactory and inadequate, as he saw the impossibility of moving beyond the impenetrable wall of the surface of things itself. He is rather interested in the ambiguity and the polyphonic messages that - according to him - may be found in the world around us. That is why while working on this series he decided to expose each frame twice. Hence on one photograph we have two successively registered landscapes of the city of £ód¼. £ód¼, therefore, is not the only palimpsest here, as the author also used the technique of the palimpsest to take the photographs. Different motifs co-exist, intermingle, show one through the other and suggest a new dimension of reception - namely, a situation that is real because woven from tangible fragments but impossible when considered as a physical phenomenon. What should we call such a situation, then? Could we say, for example, that it is "trans-real", as it moves freely through all the different levels of reality? Paradoxically, it is artificially created, in spite of the fact that it is also made accessible merely by putting images together, without any additional manipulation on the part of the artist.

Intriguing because of their ambiguity of references, enthralling because of their richness of texture, expressiveness of forms and vague beauty that may be seen in the ugliness of the decaying city - such are the photographs of the inhabitant of Warsaw, captivated by the atmosphere of £ód¼. They make up a portrait of an externalized internal existence of the city, the palimpsest of time, history and people. They are also a projection of the subjective expectations of the photographer in the face of the phenomenon which he photographs - they are like his fingerprint on the cobblestones of £ód¼ which he registers, a symbol of his own sensitivity, emotion and memory. As Lech Lechowicz once wrote: Photography means remembering something, but also somebody, since every photograph also belongs to the memory of its author (.)3.

1Rados³aw Wojnar, £ód¼ Fabryczna - fotografie z lat 2004 i 2005, author's text

2 Ibidem

3Lech Lechowicz, Pamiźę obrazów - pamiźę fotografii [in:] £agiewniki, catalogue of Wies³aw Barszczak's exhibition at Galeria FF, £od¼ 2005

Eva Milczarek

colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

colour photography , 70/100 cm

Exhibition organized as part of an

OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME

"Art Promotion"

Copyright ©2006 Galeria FF £DK, Rados³aw Wojnar, Eva Milczarek.