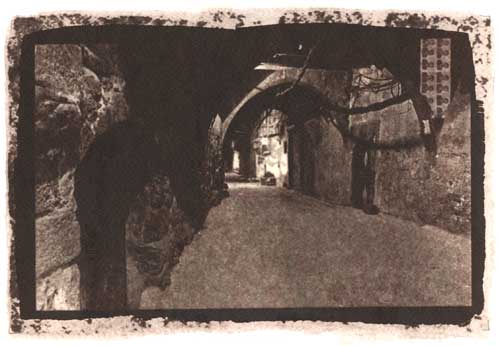

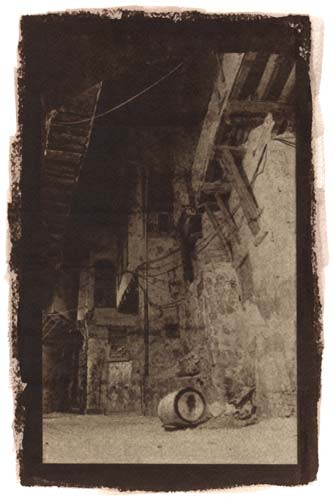

The DisORIENTation project came into being between 2003-2007. Travelling in the Middle East I breathed in the images and atmosphere of this region and carried it back to my darkroom in order to work on them some more. The resulting unique salt prints on aquarelle paper, partly photo-montages, have been treated with chemical solutions, prepared according to my own recipes.

About the project

georgia Krawiec

Travels in Light

In the course of her career Georgia Krawiec has already managed to complete a few significant artistic projects, therefore we can now attempt to describe her working methods. As far as her photographic images go, for example, the most characteristic feature is the play of the signals of modernity and archaism. Krawiec uses elements of primary photographic techniques, like a pinhole camera, analogue methods of registering an image on the negative or making prints on calotype paper which she personally prepares to this end, but in the end she provides her images with the effects that can be attributed to electronic alteration. She also takes up contemporary issues but presents them in the atmosphere of timelessness or in the context of reaching into the future. On the other hand, what in her photographs can be associated with classical standards seems to have been uprooted from its historical context and is presented as a recent intermedia impression. This contrast of opposites can be also observed when the authoress stresses that the objects presented really and physically exist, though she also uses photomontage in order to boost and aesthetically enhance representations and to transport them beyond literalness. However, she is not an artist who simply manipulates found, ready-made materials. Her creative approach to photography can be seen in that she celebrates long expositions in places in which she must be personally present - which is connected with long journeys, while the external completion of the images is closely connected with the logic and character of the experienced situation. Ultimately Krawiec achieves an intriguing visual effect where the play of the above-mentioned opposites takes place in a rather mellow, contemplative mood. Objects and situations, caught on camera to make them last as icons, are later partly dematerialized among the painting effects of the manually applied emulsion which sometimes undergoes uncontrolled processes of transformation, as the artist allows free further chemical activity of its components.

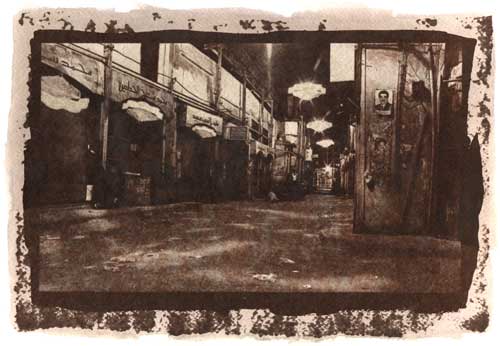

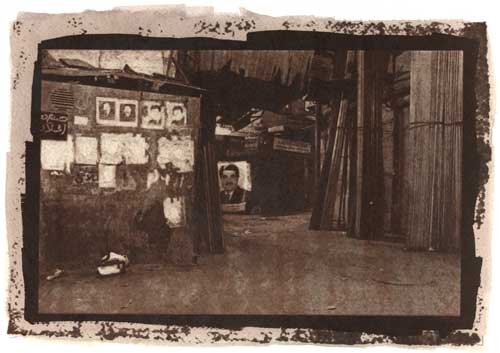

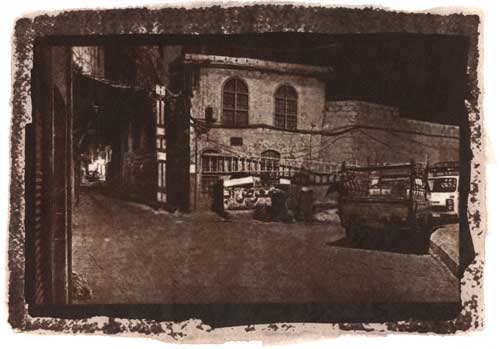

The DisORIENTation series, on which she has been working recently, consists of photographs taken in selected cities in Turkey, Syria, Liban and Iran. These are cities of historical and contemporary significance, like Istanbul, Damascus, Beirut, Teheran, Isphahan and Yazad. Although some of them are not metropolises any more (due to geopolitical changes or military conflicts), their symbolic prestige still counts. No wonder, as this region is associated with the beginnings of civilization, with special regard to the growth of cities. It is there that the oldest metropolises known to humanity came into being, metropolises that in the course of history used to be centres of different states, cultures and faiths. That is why throughout the centuries Europeans manifested their desire of spiritual renewal and discover the origins of our civilization through their interest in the Middle East. In more recent times artists of the Romantic period provoked a new wave of interest in the Orient (this term meant at the time all lands and countries between Crimea and North Africa), treating it as a counterproposition to the rationalized culture of the West. When photography appeared on the scene more or less in this period, the Middle East was one of those regions where photographers working for publishers in Paris in London travelled most often. Their illustrations quenched the curiosity of the world, evoked cultural sentiments and confirmed the feeling of superiority of societies leading the march of progress. Therefore many photographs since the mid-19th century â travel, ethnographic, archeological or news photos (for example from the Crimean War) â showed the Middle East also as the land of stagnation or backwardness. People on such photographs and their way of life seem even farther from the logic of modernity than facts of exciting archeological discoveries in Persepolis, Petra or Babylon. Cities od the East, immobilized in their medieval forms, became in the 19th century an antithesis of industrialized metropolises of the West â as they had seemingly lost their integrated and organic character due to the introduction of new communication systems, rapid growth of suburbs and the loosening of bonds between inhabitants. Perhaps that is why the oriental urbanistic model seemed to be an ideal fulfillment of the function of the city as a place with which one can identify. Its archaic concept, modified in ancient Rome and later in Byzantium, was continued in the culture of islam. It is not an accident that the current name of Constantinople â Istanbul â means simply âĆA Cityâ.

Taking up this kind of subject matter Georgia Krawiec had to take into account this tradition and its memory, but she is looking for her own way of its interpretation. Actually she avoids those characteristic features of selected oriental cities that are well-known from popular iconography or folders for tourists. She presents the landscapes she has photographed in such a way that makes them anonymous. Georgia usually photographs alleys and solitary buildings, and then confuses the receiver all the more so because when working on the prints she erases the contours of objects, makes the images look sketchy and never includes human beings in the pictures (more often than not due to very long exposition times). Only portraits of political leaders posted on the walls become a kind of a sign of human presence, although even here details have been reduced to the minimum, so that the âĆorientalismâ of her photographs does not really have its own clear-cut distinguishing feature. On the other hand, signs of contemporary uniformization conceived according to Western standards are no more visible at all. Many photographers in the past decades stressed the similarity of urban landscape the world over â seeing it as the effect of globalization â because similar groups of scyscrapers, supermarkets, highways, parking lots or billboards always look the same. However, Georgia Krawiec does not follow this attitude, either. Her photographic reports seem to reconstruct a certain archetypal model of the public space as the sphere one inhabits or identifies with. It shows places shaped solely by people, places that form a kind of a microcosm, as if independent of Nature; at the same time these forms have been clearly exploited so intensely by human beings that they can tell us a lot about the people who inhabit them. Therefore in spite of the fact that there are no people in places depicted in the photographs in question, they may be treated as âĆindirectâ portraits of local city-dwellers.

We can find those city images analogous to the portraits which Georgia Krawiec used to take before (like in the project called Germans in Poland). In those portraits she presented her models as people isolated from their environment, often including their doubled reflection and introducing dynamic manual interferences into the normal outline of the modelsâ figures. Such a message can be interpreted as a suggestion of internal differentiation of the modelsâ psyche, even though this differentiation is shown in such a way that also suggests that the people depicted in the portraits try to hide their feelings. Thus the common feature of those portraits and the urban landscape is the fact that they are both usually reduced to their basic features, tracts or rhythms which are supposed to express the internal pulse of the whole image. However, although it is determined by its characteristic form and its own limitations, it must reach to the outside, too, as such an act guarantees the existence of the image as well. This movement to the outside is suggested by combining the effects of faithful, precise and patient registration, secured by a pinhole camera and the structure of the emulsion which the artist freely applies later onto paper, using a brush. The informatively obliging documentalism of the image is thus subordinated to the subjective vision of the authoress, characterized mostly by her spontaneity and dynamism.

Adam Sobota, WrocĆaw, August 2007

Look also:

www.georgiakrawiec.net

Exhibition organized as part of an

OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME

"Art Promotion"