The Art of Photography According to Stanisława J. Woś

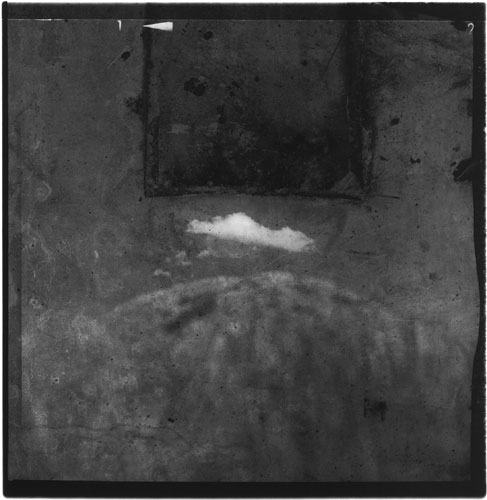

Blackness

Darkness

Light in the darkness

Light prevails

Light dies

Leaves a mark.

I leave a mark

On the face of time.

In memory of Ireneusz Eryk Zjeżdżałka

Stanisław J. Woś, september 2008

Stanisław Woś thinks about an artistic return to childhood years and his current première exhibition at the FF Gallery is devoted to this artistic and psychological problem. Who is this artist, known on the circuit since the 1980s, exploring the sphere of the graphic image, an artist whose photography is very strongly influenced by painting and who is also a painter? Let’s get ahead of the rest of this essay and say that since the 1990s Woś has become a classic of modern Polish photography, perhaps influencing new talents of the 21st century, like Paweł Żak or Leszek Żurek, although it is hard to write about it yet - since we are all under pressure of the "new document". Thus it is too early to examine Staszek Woś’s influence on artists from beyond Suwałki.

The return to the problems of childhood is very significant. It is one of those modernist questions that has not been exhausted and is still valid. Perhaps the mythology of childhood is a bottomless ocean, impossible to penetrate, define and explain because in this artistic category one works without any stable rules which - in addition - are individual and often variable. It is enough to compare the work of Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee to understand how diverse the potential of the mythology of childhood is.

My considerations will be devoted to the analysis of Staszek’s artistic career and based on his latest album called Stanisław J. Woś. Szukam światła [Looking for Light], published by Muzeum Okręgowe [Regional Museum] in Suwałki in 20071.

I. Nature - The Forest

Woś has been taking such pictures since the 1990s. Photographying the woods it is easy to fall victim to banality and routine, but Woś’s works are full of creative tension and risky. This kind of photography is the result of Jan Bułhak’s idea of "native photography" and the romantic tradition. How can this tradition be still alive? Staszek’s vision which resembles the do-called "graphic attitude" of a Czech artist, Vladimir Židlicki, and the method of photosynthesis of Krzysztof Pruszkowski, shows the mystery of nature and its eeriness which contains perhaps both eroticism and divinity. Its aim is to reveal nature’s immateriality. A religious sign also appears here - a rectangular cross, but we cannot be sure whether it actually appears or rather disappears. It is difficult to say what the tangible materiality of tree branches is because the photographed reality is immaterial. This problem has been also undertaken at the beginning of the 21st century by Katarzyna Majak in her installations and nudes.

At the break of 2007 new works have come into being called Wariacje pejzażowe [Landscape Variations] in which Woś has tackled the problem of transparency of structures and the search for geometric order. In the series entitled Wileńskie memento mori [Vilnius’s Memento Mori] the cross appears within various motifs. This mystical sign is also the symbol of salvation and everything in the photograph strives towards the cross - religious pictures on the fence confirm this observation. In this aspect Woś’s work resembles Zbigniew Treppa’s who first came in contact with the artists connected with the PAcamera Club in 1994 when taking part in an exposition called Niebo [Heaven] in which he showed a work quoting the motif of veraikon.

II. Ten Most Important Words (2004/2005)

They are Truth, Light, Beauty, Goodness, Love, Fidelity, Hope, Faith, Life and Death. One could hardly find ten other equally important words. The structure of those works is permeating and based on Kazimierz Malewicz’s famous painting, although Światło [Light] contains leaves of grass and the image of clouds. However, in most works of the series a multiplied form of a rectangle dominates. What does it mean? I have written about it in a text called Nowe symbolizowanie [New Symbolizing]2. And I believe that my analyses concerning the theory of symbols according to the gnostic explanation of Carl Gustav Jung are still valid.

III. Surreal Landscapes

They do not have much in common with French surrealism but they reveal one of the sources of Woś’s art. Actually the artist looks for a passage/channel which can also have the form of a sarcophagus. It is one of the few examples of photography devoid of manipulation or any external interference. The triptych called Obiekt [Object] resembles a little works by Tomasz Michałowski (who was one of the most talented apprentices of the PAcamera Club), although we do not have human figures here, so characteristic for Michałowski. Woś shows us a covered chair onto which - thanks to montage - two images of the sun have been projected. They gradually become smaller and turn into a human image, on the human scale.

IV. Paradocument?

Lately Woś often seems to tackle the problem of the simplicity of paradocumentary registration without using any additional effects. His series Ukraina [Ukraine, 2003] is a good example of this tendency. Woś was looking in it for simple or even "poor" structures, reaching as far back as Dutch still-life painting of the 17th century, although dynamic as far as the composition is concerned. A poor, sad world of these pictures is simple, sacred and even mystical, or at least it aspires to such a reception. Here we reach - however few of us - the artist’s most important postulate: the attempt to reach mystical states and the realization of this extremely difficult ideal in photography. Mysticism often goes beyond orthodoxy, may lead to heresy or even rejection of faith. On the other hand, it can be the road to sanctity, understanding or even contact with God and the saints. Naturally, all true art contains elements of mysticism and religious mystery, but undoubtedly this kind of artistic pratice is becoming less and less popular. However, what is interesting, the artist’s attitude of religious devotion springs not only from Kazimierz Malewicz’s suprematism but also from neo-avant-garde art of the 70s, from such tendencies or their aspects as conceptualism, from the so-called "light registration" or from geometrical abstraction. They were all formalistic in character and often materialistic. I used the word paradocument here because the effect of those works resembles surrealist painting in spite of the simplicity of style.

V. A Sign Appears (new pictorialism)

In Staszek’s photographs a manichean aspect may also be concealed - because material evil is activated in the real world. What is good and what is evil is hard to tell, looking at the works from the series called Pejzaż mistyczny [Mystical Landscape]. Personally I do not see a manichean element in Woś’s artistic and ethical attitude although maybe it is so well hidden that I am unable to detect it.

The series which comes closest to painting (though in a different sense than the pictorialism from the break of the 20th century; I have in mind manual interference here) - is called Pojawia się znak [A Sign Appears], composed of unique works that cannot be repeated. It contains extremely dynamic realizations which show the divine face of nature and even perhaps the symbol of God Himself - that is if He can be depicted at all. As a way of searching for new religious, though not orthodox iconography, Woś’s works belong to most important achievements of Polish artists, along with Zbigniew Treppa’s realizations (which are definitely based on theology to a larger extent), and Andrzej Różycki’s earlier series from the 1980s called Koszulki Panny Marii [Virgin Mary’s Robes]3.

Since the beginning of the 1990s Woś has been trying to convince us of one and the same thing. He is an artist, but a very modest teacher who spreads the most basic moral truths and prepares us for the end - of man and even the world (Dzień, w którym zgasło światło [The Day the Light Went Out, 1999]).

Woś has also done interesting mountain landscapes using prepared photography with elements of montage and negatives (Lustro [Mirror]). No wonder that his work appeared on the cover of the catalogue entitled Pamiątka z Karkonoszy. Fotografia - nowe media [A Souvenir from Karkonosze. Photography - New Media], published by BWA in Jelenia Góra in 2006, which contains touching photographs of the mistress of mood, Ewa Andrzejewska and new works by an unfulfilled talent of the 1990s, Tomasz Michałowski, who has never concealed how much he owes to Staszek Woś.

VI. Style, aesthetics and the philosophy of photography

How can we characterize those few dozen years of Staszek Woś’s career? We have to remember that the number of works is not important in art - it is the effect that counts.

Woś’s photographs from the end of the 1980s marked the search for new ways of symbolization but they were also too closely connected with the conceptual method in the sense of the study of the sign as such. Some of his works resembled the tradition of land-art which was never popular or developed in Poland. Even his later works from the 21st century are not completely devoid of this tradition. It suffices to look at the structure of such photographs as Z życia roślin - paproć (Krasnopol) [From the Life of Plants - the Fern (Krasnopol)] or Ślad (Białowieża) [Trace (Białowieża)] in order to see in them a timeless serpentine as in the famous spiral made of stones by Robert Smithson (Spiral Jetty, 1970). These realizations were so important that they were presented at the exhibition Polska fotografia intermedialna lat 80. (BWA Poznań, 1988) [Polish Intermedia Photography of the 1980s] and Spojrzenia/Wrażenia. Fotografia polska lat 80. ze zbiorów Muzeum Sztuki [Glances/Impressions. Polish Photography of the 1980 from the Collection of the Museum of Art in Łódź (1989)] whose curator was Urszula Czartoryska. Since that moment on Staszek has taken part in all most important exhibitions of Polish photography of the 20th century4.

VII. Tradition Animated by Modernity - Stanisław Woś

In the 1990s a style was born in which one may see the inspiration of the classic avant-garde but also (and that is what makes Woś so great) the tradiiton of Jan Bułhak and Edward Hartwig. In the case of the "father of Polish photography" we have to do with the love of the romantic tradition - city landscapes or their details and nature: expressive clouds, the forest or single trees. Hartwig’s graphic method is similar, though his effects are completely different. But even then Woś has worked out his own style, using diverse formal experiments over which he has always had complete control. His works, so recognizable and respected among photographers and apprentices of this branch of art still evolve as far as aesthetics is concerned, covering new territories, including the photographic document which does not belong to the foundations of Woś’s art. He has created many works of great artistic value which is a rare achievement and which characterizes only mature and successful artists.

In an interview with Krzysztof Makowski Staszek has said many interesting things, remarking that he is not a philosopher: "The presence of light and darkness in my works, their mutual relations and proportions reflect my views on the proportions of goodness - light, and mystery - darkness, both in the world at large and in life, in our existence and the psychological condition of man. The inevitability of death and drowning in darkness in the context of weak flashes of light (like faith, optimism or goodness) does not make me anxious or a rebel. In this sense I take the path of a very subjective truth. However, I never try to interpret the process of passing away (which always inspires me and makes me reflect) in terms of destruction. I can see in it a special beauty, seriousness and wise peace. I would rather that the atmosphere of darkness and certain apprehension that appears in my works be perceived as a kind of adoration of mystery"5.

What makes his photography so significant is symbolization and the search for new equivalents for this spiritual sphere which according to Mircea Eliade is called art because it is meant for people who believe. Such was the basic explanation of the meaning of art since paleolithic times until the beginning of the 20th century. In Woś’s works the philosophical and theological aspect is highly developed. Różycki investigates the sphere of folk art as he thinks it direct and unadulterated, Treppa is engaged in fundamental iconography, like veraicon or the Crucifixion, and Woś is immersed in nature and abstraction. In this way he has become, like Grzegorz Przyborek (whose work has been inspired by the tradition of plastic arts, not photography, since the very beginning of his career), a creative classic of Polish photographic art.

1The most important monographic text on Woś’s work is an extensive BA thesis written by Andrzej Górski under my supervision at Instytut Twórczej Fotografii Uniwersytetu Śląskiego [Institute of Creative Photography of Silesian Univeristy] in Opava (2003), entitled Pejzaż mistyczny w fotografiach Stanisława Wosia [Mystical Landscape in the Photographs of Stanisław Woś, 2002], http://www.wsfoto.art.pl/warto.php. As far as Polish critics go interesting essays on Woś were written by Elżbieta Łubowicz, for example Fotografia - lustro rzeczywistości. O pracach Stanisława J. Wosia. Stanisław J. Woś. Z ciemności i ze światła [Photography - Mirror of Reality. On the Works of Stanisław J. Woś. Stanisław J. Woś. From Darkness and Light]PGS Sopot, 2002, catalogue of the exhibition, and Głębia obrazu, głębia świata [Depth of Image, Depth of the World], in: Stanisław J. Woś. Szukam światła [Stanisław J. Woś. Looking for Light], Muzeum Okręgowe [Regional Museum] in Suwałki, 2007.

2K. Jurecki, Nowe symbolizowanie [New Symbolization], Stanisław J. Woś. Pejzaż mistyczny [Stanisław J. Woś. Mystical Landscape], catalogue of the exhibition, FF Gallery, Łódź 1994.

3An interesting initiative was a photographic workshop held at the 4th Meeting with Photography in Wigry called Niebo-Drzewo-Kamień [Sky-Tree-Stone, February 2008], conducted by Woś, Różycki and Treppa, and concluded by an exhibition recalling the best expositions by the PAcamera Club from the 1990s. That is why this kind of photography is still evolving, mainly thanks to Radosław Krupiński who manages the Edward Hartwig Photographic Gallery in Wigry. See Niebo-Drzewo-Kamień, Dom Pracy Twórczej [House of CreativeWork] in Wigry, catalogue of the exhibition, Wigry 2008.

4Three such exhibitions have taken place and Woś took part in them all, which obviously means that his works are important. I organized the first of these exhibitions with Hitoyasu Kimura for the Shoto Museum of Art in Tokyo and the Niigata Art City Museum in 2006; the second exibition took place in 2007, organized by ZPAF [Union of Polish Photographic Artists] - it was called Polska fotografia w XX wieku [Polish Photography in the 20th Century] (curators: Małgorzata Zyberk-Plater and Adam Sobota), while the third one was shown in 2008 during the Month of Photography in Cracow. Its organizer was Wojciech Prażmowski, the curator of the exposition Marzyciele i świadkowie. Fotografia polska XX wieku [Dreamers and Witnesses. Polish Photography of the 20th Century]. I’m especially disappointed that the exhibition organized in Japan, which required so much effort and was opened in Niigata by its new director, was removed from the exhibitional programme of the Museum of Art in Łódź in 2006, therefore the Polish audiences could not see many works hitherto never exposed. What remains of it is only a very well edited catalogue in English and Japanese, containing the reproductions of all works shown in Japan. That is why having read what Piotr Lelek has written in the catalogue of the exhibition Month of Photography in Cracow, Cracow 2008, on page 13, namely that the last such big exhibition shown abroad was Fotografia polska 1839-1979 [Polish Photography 1839-1979] at the International Center of Photography in New York City in 1979, I have to say that this simply goes to show the author’s ignorance as to the latest history of Polish photography, ignorance of which I would not suspect the organizers of an international photographic show. Not to mention the fact that the expositions in New York and Paris the author mentions were not organized due to the initiative of Urszula Czartoryska, but Ryszard Bobrowski!

5K. Makowski, [conversation with S. Woś], in: K. Jurecki and K. Makowski, Słowo o fotografii [A Word on Photography], Łódź 2003, p. 333.

Krzysztof Jurecki

Next exhibition

17.10.2008