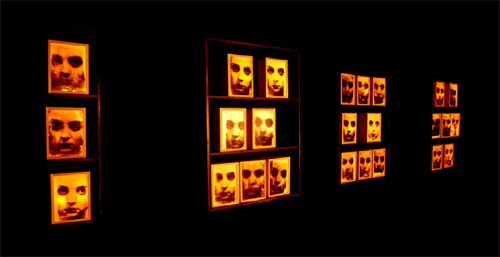

installation view

installation view, detail

installation view, detail

Self-portraits in the Face of Death

An extraordinary series of photographs on glass inclines us to think about the meaning of the cemetary in our contemporary civilization of consumption and obsession of material possessions, in which death is a taboo subject. Is the cemetary a place of eternal rest of the dead, a mark of our culture and history, a reflection of the condition and spiritual awareness of our society, or just a stop on the further way beyond the grave? The cemetary is a document of funereal customs, connected with religion. The custom of depositing the bones of the dead in ossuaries after the decay of the body is closely connected with the belief that man will rise from the dead. It is the most beautiful act of faith and hope that gives meaning to our existence. The works from this series were produced as the second part (the first being a series of paintings entitled Passing) of the authoress’s Ph.d. work called Pesach and presented at the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow in 2004.

Karolina Aszyk’s photographs from the Ossuaries series make us reflect and at the same time seem to be a light at the end of the tunnel. They are an attempt to tame death which we cannot treat disinterestedly.

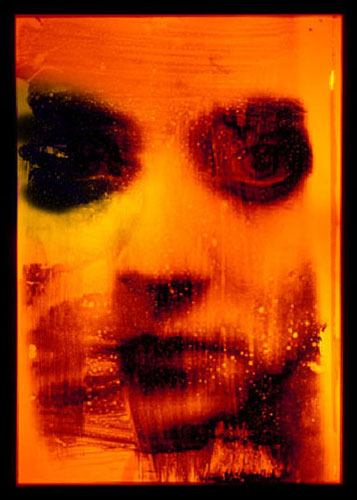

The faces of the people looking at us from beyond the glass (or perhaps reflected in it?) have been transferred onto the panes with the use of a photographic method which guarantees the exposure of the reality of being. This motif, which originated in symbolic painting, known from the drawings and posters by Stanisław Wyspiański, is still very fruitful, and was already used by Lewis Carroll in his famous Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. It was also often used by the surrealists, including a Pole - Aleksander Krzywobłocki - in the 1930s of the 20th century, and later in the excellent film by Wojciech Jerzy Has called Manuscript Found in Saragossa (1964). In its final scene the main character played by Zbigniew Cybulski finds out that he is actually in a different reality, on the other side of the glass. A question arises which I cannot answer, although it is very significant - what is a mirror in various concepts which originated in literary Romanticism?

An eminent contemporary French artist, Christian Boltanski, uses the motif of models looking straight ahead in connection with death, dying and the Holocaust, most often recalling faces of real children who lost their lives during World War II.

The Ossuaries series is a set of over a dozen boxes enclosed in glass in which the faces/souls of the dead are reflected. Their sunken, empty eyes seem to look inward, into the depths of being on the other side. It is an important motif - and a continuation of themes found in other photographs by Karolina Aszyk.

II. Self-portraits called Passing (2009).

Karolina Aszyk’s self-portraits, presented at the FF Gallery - what are they about? Two aspects of a face/soul, apparent neutrality of expression, or perhaps a mask? What hides beyond it? Is it possible to see Her as she really is deep down inside? From the very beginning of the history of photography we can see that as far as portraits and self portraits are concerned, two forces/potentials have been distuingished that compete with each other. On the one hand it is objectivism and typology, but also stage setting that strives to cover up one’s identity or create an expressive image, perhaps a surreal one in the form of a mask concealing an "identity" that can be interpreted in many different ways. All such operations are meant to uncover and present imagination. That is what Richard Avedon was doing in his works, and in Poland Krzysztof Gierałtowski.

On the other hand, we have the possibility to enter the mind/soul of the model who - if he/she wants to - can reveal his/her psyche in the true image of his/her face. Such attempts were made by Wikacy (who in the end began to doubt their efficacy) in his "sharp-frame" photographs (1912-1919), and by portraitists of creative documentary origins, like Zofia Rydet in her series called Sociological Registration 1979-1990.

Can the facial expression registered in an image or in a photograph be true and reflect the true psychological state of the portraited model? We know that life is varied and subject to constant change, and that it is difficult to grasp its decisive or constitutive image. However, we can point to some very important achievements in documenting a given fragment of life, contained in the formula of the self-portrait.

Looking at Karolina’s works I see at least two problems she attempts to solve. The first one is connected with the examination of the structure of lines laid on self-portraits or the portraits of the artist’s husband - Zbigniew Treppa. Naturally, they are not merely ornaments but something more. Those lines form a covering that resembles a spiderweb through which one has to force one’s way in order to reach the model’s true facial expression, and perhaps even true "life". Sometimes in the series in question those lines also become a form that refers to the veraicon and the image of Holy Mary’s face, although it is just a distant allusion. We have to remember that Mary’s face, so beautiful and noble in Renaissance painting in the south and north of Europe, was later trivialized. But this motif - of the mother of God and little Jesus - was unexpectedly reborn in the photography of the 1920s and 30s (Dorothea Lange, David Seymour), mainly in war and social reportages. Paradoxically the subject of war renewed or perhaps even rehabilitated one of the most important iconographic motifs of religious painting. Likewise the attempt at reaching the mystery of the veraicon makes it still one of the most important subjects in painting and photography in the 1980s and 90s of the 20th century, while the most important book on the subject, called Całun Turyński: Fotografia niewidzialnego?(The Turin Shroud: a Photography of the Invisible?) was written by Zbigniew Treppa.

Certainly Treppa and his books are an important reference point for Karolina’s works - his wife. In the works which I had a chance to see it is easy to notice an attempt at reaching immateriality, transience and also melancholy - sorrow caused by death and taking leave of this world. "Why do we feel this sorrow?" - Father Tischner, a priest and philosopher asks in the film about Stanisław Wyspiański’s melancholy. We observe and domesticate death, including the deaths of our closest relatives, but we also become aware, like Wyspiański at the beginning of the 20th century, of the process of getting older, i.e. of the fact that innocent and beautiful bodies of children are also dying.

Lines laid on the portraited faces by means of graphic operations contain a certain dramatic aspect, "separate" the faces from the viewers and create the impression that they are unattainable, closed off in a different space. They move away from us and sometimes dissolve in the infinity of being. But they are still there! And we still think of death, and still try to tame it. The light that appears in some of the works in this series is surely a symbol of religious hope for eternal life, and of the faith of the artist that such a life is possible. The relocation to the other side is a dramatic but conscious act. The faces are peaceful and express trust in the Father.

The second problem which Karolina Aszyk tackles is the search for an image in image/reality. Her photographs exist in some indefinite space, and some of them have been produced in the manner of a "modern frame".

Painting - Passing (2003-2005)

The series of ten paintings called Logos, Icon, Bread, Sacrifice, Veil, Passing I, Passing II and Sanctuary, done in a difficult, abstract and symbolic style, not only tells the story of the life and death of Jesus Christ but also tries to explain, in a theological and artistic way, the structure or the nature of the world. These paintings made me very happy because Karolina presented her theological vision in an interesting artistic form, often referring to icon painting and painting in the tradition of Kazimierz Malewicz’s art. Of course her works pose many questions that I cannot answer. In the beautiful painting called Logos we see a fissure which seems a very interesting and risky credo. The painting called Bread is especially interesting - we see a book (the Bible?) with a Greek cross and the Logos hovering over it, though we can only see its fragments. The painting has been done in a sublime style, in red and scarlet, with a certain deformation of the book/bread. Another canvas - Sacrifice I - conceptually refers to photography. It was symbolically divided into three spheres - the line of life passes first through yellow colour, then through red, which dominates in the picture, and finally through black. But the line seems infinite since its beginning and end is not to be seen. I think that Passing II shows another type or model of death which has more to do with Kantor’s art. Also, in Karolina’s works the motif of a tunnel often reappears, which is a symbol of passing through, of transformation. The series ends in Sanctuary, which here means the end of the journey in the House of the Father and marks our union with Him.

The artist usually uses rectangular forms, and sometimes, though not as often, squares. These geometrical forms overlap, now and then creating a form of a reversed cross. Aszyk consistently uses the same colours in which red and scarlet of the Logos dominate, with yellow in the background.

III. Photography and painting

In the case of Aszyk’s art (it is a pity that it is exhibited so rarely) we have to do with two concepts, expressed in two different visual languages that overlap and complement each other. Currently only very few artists are able to attain such a high level of philosophical discourse. Not counting Jerzy Nowosielski, a theologist, they are, among others, Stanisław Fijałkowski, Stefan Gierowski, Jan G. Issaieff - an artist who comes closest to Karolina’s concept of art, borrowing from the idea of a synthesis of icon painting and from Mark Rothko - and Stanisław J. Woś.

Regretfully, the Church is not interested in this type of art, like most important public galleries and national museums, concerned mainly with pop-culture. This situation is probably the result of the domination of the concept of "post-art", the belief that metaphysical art and religious man are dead - as prophesized since the 60s by French postmodern philosophy. I am certain that we have believed in those arguments too quickly.

Karolina Aszyk’s painting is very difficult because it is meant for the religious and as such is doomed to fail - since even the greatest painters of the 20th century who took up religious subjects were well aware of the imperfections of their creations. Aszyk’s explorations in Passing may cause some controversy. But an artist has an obligation to penetrate the problem of the mystery of death and whatever will take place "after" that because it has been one of the most important subjects of art since its beginning - and I believe it shall be so in the future. It still is one of the most important artistic problems, though not many artists realize this.

Aszyk’s art which I had not known before March 2009 in spite of the fact that I knew the authoress, made me very happy in a religious way. That is why I strongly recommend it to everyone who is looking for theological values in art, not simply entertainment.

Krzysztof Jurecki

installation view

installation view, detail

installation view, detail

Next exhibition

9.5.2009

Copyright ©2009 Galeria FF ŁDK, Karolina Aszyk, Krzysztof Jurecki