I photograph,

Sometimes I can't breathe.

I hide my head in a paper bag.

Colour instrument of imagination.

Sometimes I can't breathe.

I hide my head in a paper bag.

Colour instrument of imagination.

Katarzyna Kłudczyńska

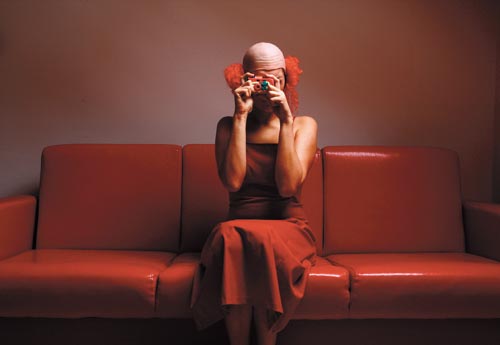

Common opinion has it that a portrait should concentrate on the image of the portraited person. Although there are many historical examples of portraits taken as a part of somewhat more built-up scenes full of characteristic attributes and symbols, and suggesting the search for interpretation beyond the external appearance of the model, it is precisely the external appearance that has always been considered to be the dominating content of the genre. The image of a face allows us, in this mode, to identify the man, the model - while its grimaces reflect the mood of the model at a given moment, when the picture was taken. But Kłudczyńska's self-portraits not only do not allow us to see her face - they also seem to be works of theatrical stylization and setting. In the photograph mentioned at the beginning of this essay Kłudczyńska hides her face behind her camera and hair. In another picture the head of the model is hidden under a paper bag, and still elsewhere the authoress hides her face under a toy-mask, a plastic bag or a hat. In each case her face is masked and concealed, but it is not the only kind of camouflage at work in Kłudczyńska's self-portraits - as she also hides in the "crowd" of her own digital clones. That is why in some works we see 2, 4 or even 5 similar figures, multiplied by Kłudczyńska. Subtle differences between them puzzle the viewer, but not seeing the faces he cannot even be sure whether they are even figures of the same person. Unlike traditional portraits which situate the model in a real or fictional context, Kłudczyńska's works make everything seem unreal. Multiplication, masking and theatricality allow the artist to project a completely new and unconventional image of herself, one that escapes categorization and superficial analyses.

Kłudczyńska's self-portraits are not about whether a photograph shows the true, real and natural person, but they rather register the image of a character, persona, created especially for the sake of the photograph. Like an actress, Kłudczyńska plays fictional characters and puts on various masks, hiding from everyday routine and reality. That is why her self-portraits are a continuation of the tradition of the so-called "masked self-portrait" in which the artists did not show themselves directly and literally but rather tried to hide from the viewer, playing the role of only one of the participants of the given scene.1 So in case of Kłudczyńska's works, like in most such traditional masked self portraits, the artist appears in the picture but sort of remains in hiding.

Masking her real, true face Kłudczyńska defies everyday reality and ordinariness, but it does not simply mean that she puts on a mask in the most literal way. Hans Belting writes about putting on a mask that we always do it when we put on any conspicuous attire that defies the norms and standards of a given culture or society.2 Such garb thus lets us challenge the accepted convention. Although make-up and everyday clothes are also a kind of mask, Kłudczyńska clearly and intentionally rejects ordinariness and "street masking codes". Claude Levi-Strauss sees the sense of the mask not in what it presents but in what it transforms, that is in something against which it presents, whatever it presents, and which it substitutes at the same time.3 In Kłudczyńska's self-portraits it is her external appearance that is transformed and against which her act of masking herself is directed. In this case the face - or rather faces - of the artist we get to see have much in common with the notion of the carnival, of a feast which lets people reject everyday reality and introduces some short-lived although radical social and individual, personality changes.

The participants of carnival rituals put on masks in order to change their identity and become one of the carnival characters. The carnival is "the world upside down", the time of unusual rituals and events. During the carnival everything is mixed up - women change into men if they dress up as men and the servants play the roles of feudal lords. In spite of the fact that the carnival masquerade offers its participants a chance to change momentarily into somebody else, someone one is really not, another aspect of the carnival gains significance here, connected with the liberation of our needs, usually concealed under the cover of everyday life. The carnival not only lets us play somebody else but also reveals "the other" in us, usually hidden in the subconscious desires of every human being. Rational ordinariness of every day life is then replaced by an irrational ritual; all that is ordered and Apollinian undergoes a short-lived change into its chaotic Dionisian opposite.

Kłudczyńska's self-portraits sometimes seem to penetrate the nature of her Dionisian alter ego. Her double self-portrait in which we see two naked figures with masked faces allude to the carnival masquerade most openly - as well as to its celebration of freedom or release. In another work from this series the artist sits on a red leather couch in a room with sensual half-lighting - but her carnival behaviour is not to be attributed to the fact that there really is a holiday, a carnival going on. The main reason for her masquerade is the presence of the photographic camera which somehow conducts the personality change and allows the liberation and transformation of the model. Seeing a camera pointed at us we become somebody else and show our other, unknown and sometimes complex face.

Gaston Bachelard conceived the mask to be a simple synthesis of two very much related opposites: dissimulation and simulation.4 In Kłudczyńska's self-portraits her external, everyday self is being dissimulated while her other self is being simulated. The phenomenon of the synthesis of dissimulation and simulation of which we are speaking here also concerns the dialectics of concealment and revelation. For example, in one of Kłudczyńska's self-portraits we can see her naked, i.e. revealed, uncovered and doubled body that is a counterbalance for the her other faces hidden under the mask. The relation of the hidden/covered concerns also Kłudczyńska's another self-portrait in which the role of shelter or covering is played by� house-plants which as if block the access to the naked female body of the artist. In another work Kłudczyńska presented "two versions of herself" - dressed and undressed at the same time. The dialectics of what is covered/revealed, dressed/undressed, covered/uncovered and finally masked/unmasked determines the way in which Kłudczyńska presents herself in those self-portraits. Here the very process of photographing becomes extremely significant as it is based on a similar dialectics of opposites. In some works the camera even plays the role of a mask that covers the model's eyes. However, the effect is rather illusory as the camera is actually an instrument that facilitates the observation of the world and offers a sharper view of reality.

A photographer has the capacity to look. A camera at his or her eye gives him or her a symbolic covering - since at least one of the eyes is covered. People around the photographer can never be quite certain what he is looking at. As an observer, a photographer has the right to choose, but he also has control over the observed, the model, subjected to the photographer's manipulations and without much influence on hisor her decisions. The relation between the photographer and the photographed - which can be compared to the relation between the hunter and the hunted - radically changes value in the case of a photographic self-portrait because in the latter situation the photographed is the photographer, executioner and victim, his own subject and object at the same time.

In the tradition of the self-portrait as genre artists sometimes depicted themselves with the attributes of their craft. While a painter can imagine himself with a palette, easels or a brush, a photographer naturally presents himself with a camera, in many cases registering its presence in the mirror. Regardless of how Kłudczyńska's self-portraits came into being, the many cameras pointed at the viewer make us aware of the moment when the picture was taken, when the artist "was pointing at herself" in an invisible (for us) "mirror", aiming as if she were holding herself at some "photographic gunpoint". Moreover, in Kłudczyńska's works cameras are ambiguous objects that can be used both as means of defense and aggression. This is probably best exemplified by the double self-portrait mentioned above, showing the artist dressed and undressed at the same time. In both versions the model holds a photographic camera over her private parts, first as the instrument of control and then as something that protects and covers her privacy. Although all her self-portraits come into being as the result of Kłudczyńska's self-scrutiny, her looking at herself, the public might get an irresistible impression that they are watched and observed. In other words, it is not the spectator who watches the artist, violating her privacy like a peeping Tom, but it is rather the artist who watches the viewer from a safe, literally interphotographic perspective. This is especially true about the many versions of the self-portrait taken in the nude but masked by house-plants and showing figures who look at the viewer from a voyeuristic position, through strange, toy opera-glasses. The vegetation allows for camouflage and shelter, while the binoculars offer a safe point of view and give the artist control over the viewer. Thus even seemingly innocent, innocuous instruments/toys may become weapons, pointed at the viewer.

Witold Kanicki

2 See H. Belting, Antropologia obrazu: szkice do nauki o obrazie, transl. M. Bryl, Cracow 2007, p. 45.

3 See C. Levi-Strauss, Maska nie istnieje sama w sobie, [in:] M. Janion, S. Rosiek, Maski, vol. I, Gdańsk 1986, p. 72.

4 G. Bachelard, Fenomenologia maski, [in:] M. Janion, S. Rosiek, Maski..., op. cit., t. II, s. 14-24.

Copyright ©2010 Galeria FF ŁDK, Katarzyna Kłudczyńska, Witold Kanicki