|

|

|

|

|

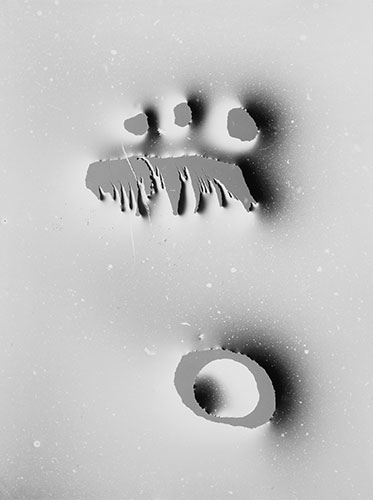

Untitled, 1957-1959 heliograph on matte paper, 23.3 x 17.8 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, [1959] heliograph on glossy paper, 23.9 x 17.9 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, [1959] heliograph on glossy paper, 24.1 x 18.3 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, [1959] heliograph on glossy paper, 24.1 x 18.3 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

| Marek Piasecki. A Photographer among Painters. | |

|

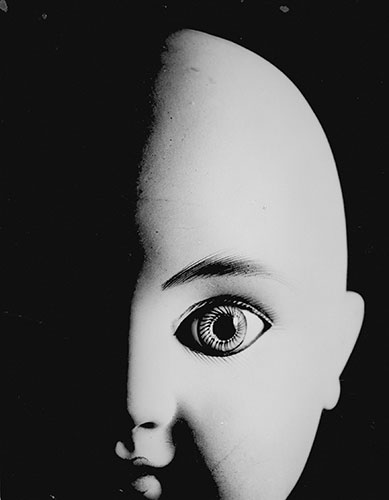

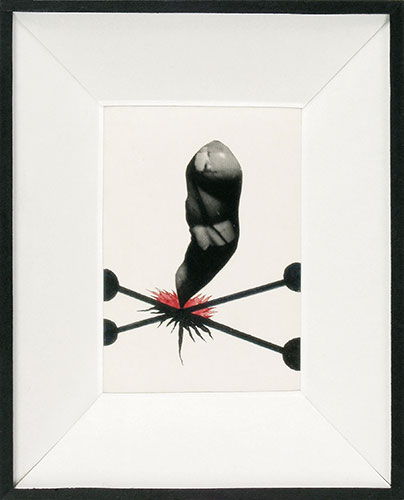

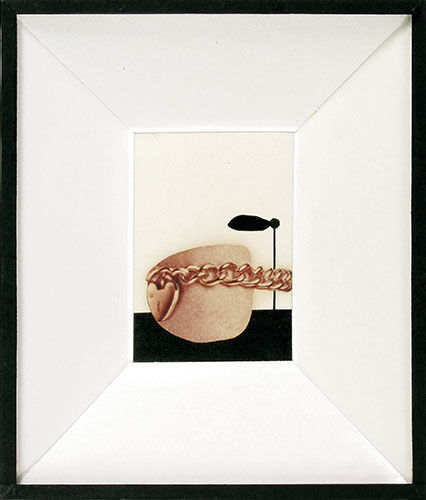

After controversial feats of artists who followed critical art and after lukewarm pop banality young artists became interested in introspection. Art as expression of "the artist's soul" and the search for form yet again started dominating on the Polish exhibition market. Young surrealism - since this is the trend in question - uses mainly traditional techniques, especially painting and drawing. The FF Gallery presents the achievements of one of the most interesting photographers of the second half of the 20th century, Marek Piasecki. His art is an example of one of those unique styles in Polish art history that stand between surrealism and neodadaism. Piasecki's surrealism is devoid of Freudian connotations and it does not pretend to discover subconscious contents or displaced traumas. It rather calls to life self-sustained, poetic microworlds by way of artistic experiment. This latest presentation of Marek Piasecki's accomplishments has been made possible thanks to the efforts of Starmach Gallery, efforts which led to the editing, cataloging and putting on public show the works of an artist marginalized in the discourses of art history for years. The most comprehensive presentation of Piasecki's art to date took place in Zachęta in Warsaw at the break of 2009. Exhibition called Fragile revealed the many aspects of Piasecki's art - he is not only a photographer but also the author of objects, sculptures and assamblages. Thanks to this exhibition it also became clear that Piasecki, next to Jerzy Lewczyński and Zdzisław Beksiński, created black realism photoreportage. Piasecki for years documented the life of Miron Białoszewski and the theatres established by the poet: first Theatre at Tarczyńska Street and then The Separate Theatre. Critics claim that this could have influenced the poetic aura of his works of creationist photography. But Piasecki is best known for heliography. He worked out his fully original and recognizable style at the end of the 50s of the last century. The motto for this section of Piasecki's art could be a part of Alvin Langdon Coburn's ponger statement: "Why, I ask in all seriousness, must we always take common, unimportant pics of objects that can be classified into conventional groups - like landscape, portrait or figural studies? Think of the joy of something that refuses to be classified and in which you can't tell the top from the bottom"1. Working on heliographs that differ depending on the method of employing light-sensitive material, Piasecki arrived at soft, fluid shapes, resembling simplest life-forms watched enlarged under a microscope - or at somethat more aggressive, geometricized constructions. Both, however, are dominated by the poetics of understatement. And though many of those compositions were titled by the author (Second Seacat, Landscape etc.), the titles are not meant to help intepret the contents but to emphasize their autonomy as self-sustained aesthetic worlds: because in fact Piasecki's heliographs do not invite to be interpreted at all. They are enchanting in their conciseness and elegance of forms and do not express extra-artistic contents. This "chemical" painting, as Piasecki himself called it, was created in order to arouse emotions and aesthetic feelings. That is because heliography was the art of creating and selecting the best possible form; the art of creating a photographic image par excellence. Piasecki's art combines two attitudes about which Urszula Czartoryska wrote when analyzing creationist photography: the attitude of an experimenter looking for the language of light of highest plastic standards and the attitude inclined towards expressive and poetic values2. As images that stand between photography and graphics Piasecki's heliographs are pictorialists' dreams come true since photography becomes an art form here. As far as of pictorialists are concerned we can notice the influence of preraphaelite painting in their works, but Piasecki's art should be analyzed in connection of the art of the 2nd Cracow Group. That is why the closer presentation of the context in which Marek Piasecki worked demands that we take a trip to Cracow between the two great world wars, in the 1930s. The Cracow Group was active between 1930 and 1937 as a formation of students who opposed the politics of nationalism that dominated in Poland at the time. Although all members were fellow-travellers of the political left, it would be hard to find any direct manifestations of such sympathies in the works of any of them. The Group had no artistic programme and never issued a manifesto. This informal association of painters closely studied the avant-garde art of cubism, surrealism and abstractio, and such influences can be seen clearly in the works of leading representives of the group, Jonasz Stern or Maria Jarema. After World War II the tradition of the Cracow Group was continued by the Group of Young Artists which in 1957 adopted the name of the 2nd Cracow Group. Marek Piasecki, an art historian, joined their ranks in the same year. The informal leader of those artists became Tadeusz Kantor, and their headquarters was Krzysztofory cafe. Abstract tendencies, characteristic for the 2nd Cracow Group, the influence of surrealism and art that ignored the rule of mimesis, often conducting formal experiments, were all analyzed by Andrzej Kostołowski in an article called The Cracow Group: Strangeness and Hallucinations. Kostołowski claims that three main factors were responsible for what the Group was. Firstly, Kantor's charismatic personality, through which the Group received "dictates and propositions derived from the morals of the avant-garde, from the early post-war echantments with surrealism (...)"; secondly, the climate of Cracow with its unique, magical and wonderful genius loci and thirdly the real world in the Polish People's Republic that "incited artistic escapes and withdrawals"3. The influence of non-figurative painting on Piasecki's heliographs seems obvious. One of them could be even taken for a black-and-white reproduction of Maria Jarema's painting. Piasecki shared his interest in organic and abstract forms with other artists of the Group. We can see such forms, for example, in numerous paintings by Jerzy Skarżyński, Alfred Lenica or Jerzy Tchórzewski. However, we cannot speak of mutual borrowings, as each of the artists mentioned above remains an original voice. The uniqueness of Piasecki's works in this perspective is achieved mainly by using a different artistic medium and a different scale. The dynamism of the above-mentioned abstractionists, however, comes from the way of using colour and combining unusually dark, almost black fragments with strongly saturated reds, greens and blues. The art of his colleagues was definitely extravertic. Piasecki remains more intimate, while small dimensions of his heliographs actually force the viewer to adopt a contemplative attitude. In contrast with the art of another abstract photographer belonging to the group, Andrzej Pawłowski, and with the earlier heliographic works by Karol Hiller, they come closer to Bauhaus experiments in the mode of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Objects are much more prone to interpretation than heliographs. Piasecki composed them like collages and used mainly fragmented bodies of dolls. They resemble scenes from the cinematic anti-utopia by Piotr Szulkin called Golem, in which the motif of a doll became the symbol of a totalitarian system about to fall down. The attitude suggested by the repeated motif of a defragmented body and critical of the state of our culture, brings this sphere of Piasecki's art closer to his ideologized photo-reportages which he published in the weekly "Tygodnik Powszechny". As we know, black realism attempted to show the dark sides of social reality. A "committed" reportage was built using dynamic frames that emphasized the emotional relationship of the author with the reality he registered. In Piasecki's objects wherein dolls are used a gnostic note also sounds. The human body is symbolized by a toy, therefore its plastic and fragile form, all its charm notwithstanding, must lead to the depreciation of the value of sensuality. On the other hand in Piasecki's objects we can find parallels to Kantor and his affirmative attitude towards everything degraded and sentenced to death. Perhaps what is most interesting in Piasecki's art is precisely his constant balancing between affirmation - of art, of reality and of society - or denial, revolt and flight. | |

Przemysław Chodań translation by Maciej Świerkocki |

|

|

1 Cyt.za: Czartoryska Urszula, Plastyczne przygody fotografii [Plastic Adventures of Photography] Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, Warsaw 1965, p. 58.

2 Ibidem. 3 Andrzej Kostołowski, "Grupa Krakowska: cudowność i przywidzenia" ["The Cracow Group: Miraculousness and Hallucinations" [in:] Grupa Krakowska 1934-1994 [The Cracow Group 1934-1994], Narodowa Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Zachęta [Zachęta National Art. Gallery], Warsaw 1994, pp. 17-18. |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, also known as Doll, 1959-1967 black and white photograph on glossy paper, 10.7 x 8.5 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, [1962] collage, 19 x 24.7 x 3.5 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Untitled, [1962] collage, 19,5 x 16,5 x 4 cm property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

|

|

|

Spatial Composition, 1969-1975 wood, glass, dimensions variable property of the Starmach Gallery |

|

Copyright ©2010 Galeria FF ŁDK, Galeria Starmach, Przemysław Chodań |

|