|

|

|

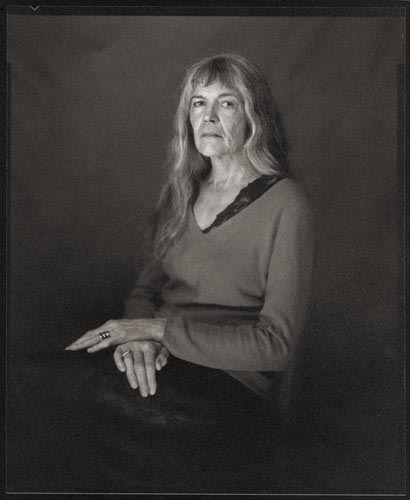

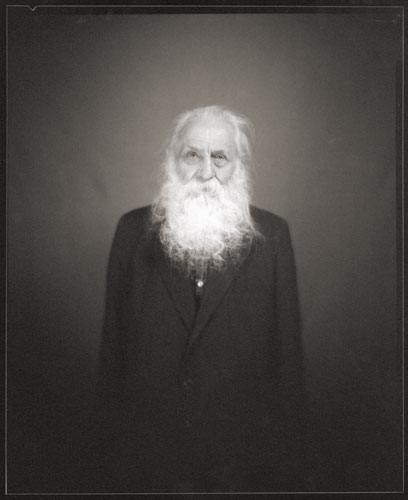

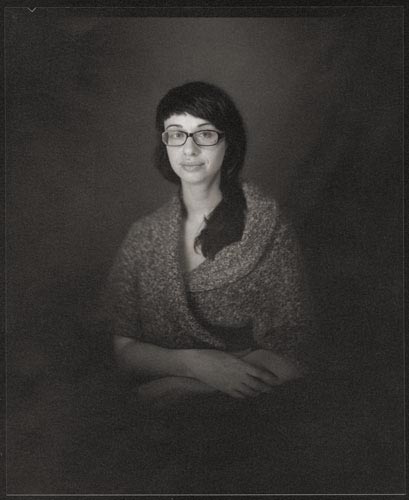

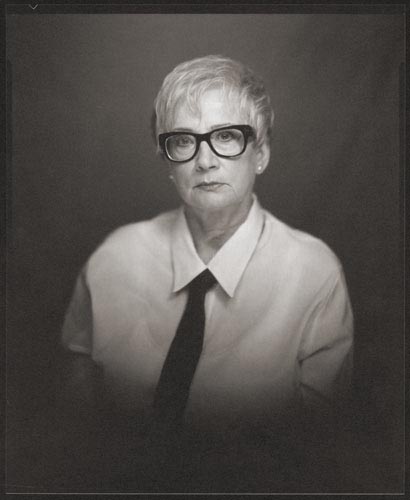

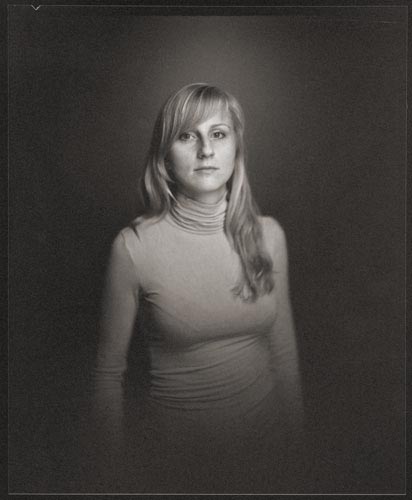

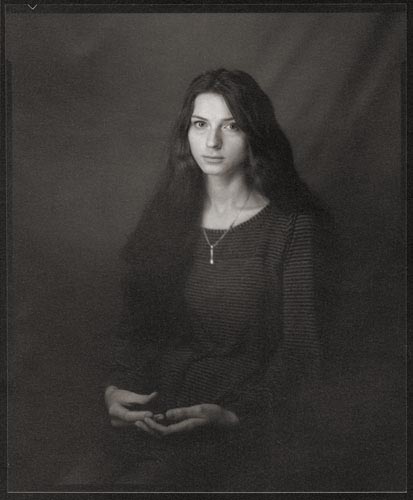

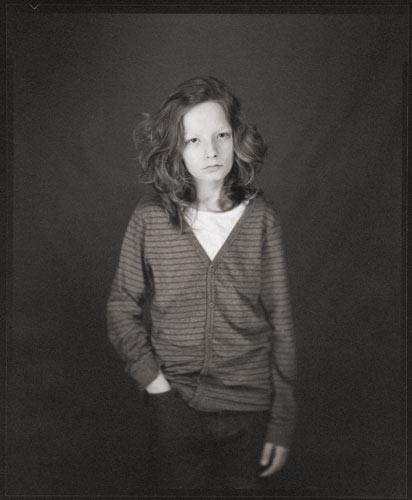

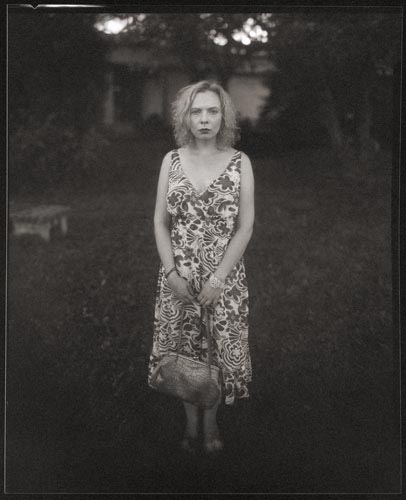

| I remember my first portraits on large-format plates from the beginning of 2010. A 19th century camera came into my hands on its way from some studio in Genoa by way of Rafał Biernicki’s workshop in Sandomierz. Old optics differed a lot from contemporary optical technology and it presented a lot of technical problems that were difficult to solve at the time. There was no shutter. I had to establish the light for the ancient glass I fortunately happened to come by. My Voigtlander-Petzval from the middle of the 19th century belonged to Stanisława Siurawska, one of the oldest photographers from Lublin to whom Ludwig Hartwig dedicated a memorial photograph, writing on the back: “with admiration”. How such a valuable glass came into the hands of Siurawska I shall never know. All that is left for me to do is to complete the story which could have started in Białogard right after the war. Large-format plates were alien to me, I was uncertain how to work with them. Sometimes it was difficult to know how sensitive they were, how long ago their expiry date expired and in what conditions they were kept. The European standard in the format of 24x30 cm was almost completely withdrawn from the market. The only plates left were those that photographers kept in private stock. Almost from the very beginning I decided to arrange portrait sessions and photograph people. I did not want to turn the lens towards still-life. My decision had to do with the necessity to stay eye to eye with the photographed person, often from the moment one inserted the film into the cassette until the development of the plate. Therefore one session could take up to a few hours. I quickly noticed that there was something going on during these sessions, not counting the photography itself, as if it was merely a pretext and not the aim of the session, although each of us anxiously awaited the image which ultimately crowned the whole encounter. Technique was not without meaning here. It slowed the whole process down and made me submit to the passing time. Nothing could be speeded up. But this stoppage offended the photographed person rather than me. It was he that silently remained in front of the camera for a long time, in the silence of the modestly lit workshop. Resting his head against a metal headrest placed exactly behing him he was looking into a large lens. What did he see in it? His own image turned upside down. How did he react to my presence? I was covered by a big piece of black fabric and I emerged from under it when there was something to correct on the set. We rarely spoke at the time because it interrupted my work. I had to be very careful and precise, which required concentration, otherwise mistakes were made and then I had to do everything again. Such sessions turned into conversations that accompanied the development of the films which I kept turning rhythmically in a big drum on wheels (something I always associated with mantra). I understood that such a way of producing portraits is most direct of all, and that photographic sessions allow the photographer to open onto the model and vice versa.

When at the break of March, 2010, Marek Szyryk invited me to take part in his classes devoted to the wet collodion method I decided to use it in my own sessions and to produce my own negatives. Many plates came into being at the time but today I can accept but a few of them. I could not find the reason to use this method while working on my portraits and I returned to the plates I could cut. But the collodion process let me have more freedom in my work, it was a great lesson of patience and manual dexterity, and most of all it took my imagination for long walks. Thanks to this process (and to the literature of the so-called Young Poland which I was also reading at the time) I confronted the problem of spiritism in photography which became the source of my subsequent inspirations and photographic adventures. When I started to assemble these portraits together I noticed that they were extremely individual and that the images strongly influence not only the people I portrait. I assumed that my portrait activity ought to last for three years. I imagined a great portrait gallery of completely different faces – different in spite of the fact that I was using the same means and instruments every time. Each of these faces is a different story, they are different worlds that can sometimes meet in the street of one city. For some time now I have been collecting photographic papers that I received as gifts from my older colleagues. The largest set of such invaluable papers came from Jan Magierski with whom we were transporting our studio in the summer of 2010. They were produced a dozen or a few dozen years ago and their date of expiry also belonged to the past long gone. These papers were much different from those produced today, especially due to the layer of silver, their weight, texture, tone, the scale of registering details and different shades of gray. The double thick Kodak Polymax Fine-Art, the Agfa MCC 118 and the Agfa-Gevaert Portiga-Rapid were perfect to make copies from my plates, developed using the formulas invented by Wojciech Tuszko and noted down by him in a text written to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the invention of Rodinal. I easily accepted the low contrast and various shades of gray instead of blackness; in fact I felt quite nostalgic about them due to my contacts with Bogdan Konopka and his photography. This was my last chance to be able to work using such fantastic materials from the past and to make them useful. Because they were portrait materials which – it seems – shall never again return to photography. This exhibition, not counting its simple title, should also have a dedication, like those photographs that were once signed on the back. Therefore I would like to to dedicate it to all of my models with whom I had the opportunity to exchange glances. Is there anything else that better preserves the trace of an encounter of two people than their memories - and photography? |

Marcin Sudziński December 2011 |

|

|

|

|

| Patina-covered Portraits |

|

The history of photography almost since the beginning has revolved around an overwhelming desire and need to create images of human beings. This is partly the result of the technical capabilities of photography, but probably not only that. We might suppose that people quickly realised that it was a medium as if ideally suited to replace the painted portrait with a photograph. Time needed for its making was not without meaning, but to a large degree also the “objectivity” of the picture, and later also the possibility of its copying – and therefore, its price. To this attitude and this kind of concept of one of the functions of photography we owe those wonderful daguerrotypes from the second half of the 19th century, made by, for example, Albert Sands Southwort and Josiah Jonson Hawes – Americans whose Boston portrait studios were once visited by almost the whole élite of this city. A similar approach was adopted by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson – Scots who not only portraited the high society of Edinburgh but also the inhabitants of a fishing village. New technology which flourished amazingly in the 20th century offered new possibilities to portrait photographers. Yousuf Karsh, Arnold Newman, Irving Penn or August Sander – to mention but the most prominent artists – have left us an extraordinary and invaluable legacy. But other eminent artists (Edward Steichen, Man Ray, Alexander Rodczenko), although portraits form only a small part of their body of work, turned their cameras to photograph their friends - which lets us gain more knowledge about them, not to mention the artistic value of those works. The portrait tradition did not exclude Poland, either. Karol Beyer, Walery Rzewuski and later Witkacy are undoubtedly outstanding portraitists. The history of photography and, of course, the history of Poland owes a lot to them. We certainly could list many more names of photographers who took portrait pictures. Every one of them contributed or contributes quite substantially to the history of portrait photography, if not artistically, then probably historically and cognitively. Therefore we should presume that portrait photography is in good condition, and perhaps thanks to digital photography we now have a chance to do what August Sander failed to achieve – to portrait the whole world. But would it really be the image of the world? Personally, I doubt it. So what makes photographers - who are aware of this kind of limitation - keep taking portraits? What keeps them interested in this branch of photography, undoubtedly difficult, which demands unusual concentration, experience and patience in relations between the model and the photographer? It is a sphere of activity on the part of the artist who, we must admit, creates reality (although sometimes to a minimal degree), but who is also automatically subjected to its (reality’s) influence. And to the most tangible degree, too – because it is the influence of another human being. So what strategy should a photographer adopt and how deeply can he interfere in the picture when taking it on the set? Indeed, a portrait is a new challenge every time. It contains the concrete social position of the photographed man, his moral attitude, experience, weaknesses, complexes etc. It is also a mysterious desire and longing for the photographic image to hide the real or imaginary faults of the portraited person. Considering such numerous problems that the photographer tackles and has to solve (usually on the set), is it possible that we might have some universal, infallible key at our disposal? Some kind of a skeleton-key to the human soul?

I do not suppose that a psychologist’s advice might bring an expected and positive result here. It seems that one of the features a portrait photographer should have is intuition and the ability to listen to other people. When he combines these features with a good photographic technique he gets a chance to make his creative idea come true. Having observed Marcin Sudziński’s work during the last few years I have become convinced that he possesses these features to a sufficient degree to continue his photographic project which is supposed to last for a few years. Who are the people that he photographs? There is no common denominator for them because their age, profession, interests and even the degree of the intimacy of their relationship are very different. A large group of these people are Marcin’s acquaintances. Another group is made up of people whom he considers (for reasons known only to him) to have such interesting personalities that his momentary fascination in them has lasted until now. He also photographs public figures, being obliged to do so because of his job. And they form the third group. So is it possible that so extremely different people can obey the rules which the photographer sets down and that his personal imprint can be seen in their photographs? The portraits presented at this exhibition prove without a doubt that it is possible. They are a kind of discourse between the photographer and his model, the study of mutual acceptance and extraordinary confidence. To a large degree it is due to the wooden, large-format camera, a minimal number (or the complete lack of) props, modest lighting and the relative freedom of the model (Marcin as a rule never imposes anything on the photographed person). It is the use of this kind of camera that has become the key to the beauty of the passing time which the people who are photographed may take in. Photography has become for him a ritual, a kind of a 19th century performance. Sometimes the photographed person has a chance to take part in the alchemical processes of getting collodion plates ready. The awareness of being in a time machine works like a drug but it also stirs the imagination - of the photographer and of the photographed models. It is also extremely important that Marcin Sudziński feels the collodion traps, feels their often superficial charm and fortunately does not use this technique at all costs, although he does not avoid it in justified cases. And there is one other characteristic feature of his photography; because at least as far as I am concerned, I cannot see any vital differences between the photographs taken by Marcin in the studio and those he takes outdoors. In both these kinds of photographs time is not measured by an electronic clock but by a sand-glass. The people Marcin portraits (regardless of their age) seem to be unhurried. And in order that no one should have the slightest doubt as to the nature of those pictures, the author, employing his impressive technical skills, immediately covers his photographs with patina. As if he wanted to embalm them at once and save them from the influence of time. |

Lucjan Demidowski Motycz Leśny, 09.12.2011 r. |

|

|

|

Copyright ©2012 Galeria FF ŁDK i Autorzy |