|

|

|

|

|

|

|

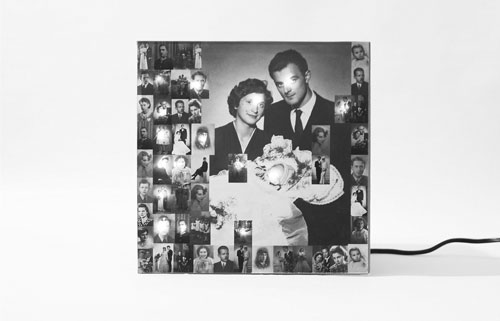

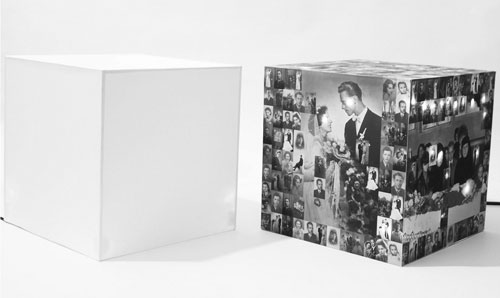

| The Props of Memory |

| The quest for the roots of one’s own identity is a private and personal, but at the same time global affair, because it sometimes involves whole social groups. Attempts at describing the nature of this continuum which places our existence within the field of various intelligible temporal and spatial conditions, as well as one’s identification with a concrete social structure, are, among others, those activities that most contemporary artists focus on – artists who feel the need to define themselves in our more and more chaotic world of changeable and doubtful values. Their other motivation is a justified fear of solitude – not so much immediate solitude, connected with our personal, private life, but the kind of solitude that results from the feeling of our growing anonymity in the steadily increasing population of nearly seven billion people. Such fear may be also additionally justified if we take into account the excess of information, typical for our times, and the white noise which accompanies its transfer. Katarzyna Krakowiak made of the quest for her own identity not only a kind of self-therapy for her own benefit, but she also managed to universalize her message, creating references accessible not only to her generation but also to any sensitive human being, subjected to the unifying influence of contemporary times. Krakowiak adheres to this tendency in art which is based on something like a special dissection conducted on the nature of our personal memory: the primal one, confirmed by our own participation in it, rooted in the memories of the past, especially childhood, but also the indirect one, reachable by means of old family photographs and various objects that were once useful and practical but have now become merely vehicles of recollections. Jerzy Lewczyński, Wojciech Prażmowski, Mirosław Bałka, Tadeusz Kantor and Christian Boltanski are just a few artists whose work seems to be an inspiration for the young artist from Łódź. Marcel Proust in his elaborate reminiscence which started from the taste of a madeleine, produced a rumination several pages long, building a whole stream of associations over a seemingly trivial event like the consumption of a cookie. Involuntary memory that lies at the foundation of such reflections is based on a series of chain-like, mutually determined associations. Katarzyna Krakowiak has been working on these tiny manifestations of existence resembling the aforementioned Proustian recollection for a long time now, since the beginning of her studies, concentrating on those trivial props that accompany us in everyday life. Old photographs also may be treated as such props, not only because they are representations of the appearances of people and things, but because photographs are also objects in themselves, often scratched, faded, with visible traces of the passage of time. “I can only turn a photograph into rubbish: throw it into a drawer or a waste-basket. A photograph not only shares its fate with paper (it is easy to destroy), but it is also mortal even if it is placed on some more durable material.” Roland Barthes points out that the odium of disapperance, of passing, and finally of the death of the substance of the photograph itself is automatically transferred onto the contents it conveys. The more beat-up the picture is, the more fragile seems the memory of the person in it. And the more valuable, since the fading picture seems to desperately cry for its further existence. The intimate collections of memorabilia introduced into the public space create a special kind of space-sacrum, which on the one hand is a sentimental memory, and on the other a conscious artistic construction that becomes a monolith of a deliberate and thoughtful exposition which, the illusion of time travel notwithstanding, is supposed to lead to a visible and clear conclusion. Objects like an old pram, an old infant’s identity tag bracelet or a lock of hair cut off many years ago are not only the source of memories; they are also lay relics that confirm the transcendent dimension of the artist’s quest and become an effective catalyser for the broadening of our well-rooted self-awareness. Although photography dominates the exhibitional space here, it seems to speak to the viewer very softly. That part of the family ethos which is connected with the identification of people and situational recognition in the pictures is automatically put in parenthesis. This aspect of the show will always remain a mystery to us. The authoress realizes that from the point of view of these particular photographs the context of place is less, and the context of time more meaningful. This is the most important, but at the same time universal level of communication. The thing is to explore one’s own experiences, intimate and unclear for those around us, and to build on their basis a reality which would take on rather the form of symbol than a narrative. Francois Soulages expresses this problem in an extremely blunt way: “These three orders – time-space-feeling – are interconnected. Photography reveals this even in its most universal dimension, but most of all through its extraordinariness, i.e. through a new kind of arrangement, by the provision of form and by making the work a work of art.” This “new kind of arrangement” is in this case, for example, the formula of the exhibition which is based on the convention of installations, photographic objects and special assamblages which use old photographs. For an orthodox follower of photography as such, this practice may seem to be an attack on the autonomy and subjectivity of photography which took years to establish, because it had been seen rather as technical, thoughtless registration than as a subsystem of art in its own right. Katarzyna Krakowiak understands this autonomy and other significant features of the photographic medium as a certain axiom which does not need any additional verification or further confirmation. It is worth adding here, by the way, that the fact that Krakowiak has used (for objective reasons) photographs from “the times of paper and silver” confirms the special authenticity of photographic representation. Here is what Andre Rouille has to say about this problem: “Traditional photography functions like a machine for freezing the image, as an instrument which allows us to produce something stable and as an updating machine. Shutter photography catches and immobilizes a gesture, a moment, the negative and the print freeze the objects of this world in a material form, while the fixer is a product which blocks all the possibilities of change in the image. With the advent of digital photography, all starting points and constants disappear. While images are still the emanation of contact with the objects of the world, digital registration tears them away from their material base.” The power of the influence of traditional photography, also called analogue photography, which is so evident at this exhibition, also results from the celebrative, even ritualistic character of taking photographs in the past – usually such pictures were later carefully kept in an appropriate album, being the invaluable treasury of family tradition. This whole exhibition is a metaphor of such an album whose special exemplification may be also found in Katarzyna Krakowiak’s book art, an art form she has been pursuing for a long time now, and quite successfully, as Krakowiak ranks very high among contemporary Polish book artists. References to literary and artistic provenances in works enriched with photographic elements seem to favour especially the creative temperament of the authoress of this exhibition. What is more, we ought to emphasize here that photography both in its form and content, i.e. with its whole media specificity, is for Krakowiak most of all raw material, an instrument of art. The stylistic convention adopted by the artist proves that she comes closer to artists’ photography than to the art of photographers. Rouille defines the first one as follows: “The prime aim of artists’ photography is not the reproduction of the visible, but making visible this something which belongs to the world but not necessarily to the catalogue of visible things.” The essence of the individual and collective consciousness belongs to the catalogue of things invisible which nevertheless manifest themselves in material and intellectual man-made products, including art. The value of Katarzyna Krakowiak’s art lies in the fact that it makes the viewer realize how unique and subjective every human being is, which in the face of inevitable globalization may and should become the introduction to the construction of effective mechanisms that would oppose those forms of political, economic and cultural influence leading to the depersonalization of human existence. In my opinion this is the main message of this exhibition. |

Piotr Komorowski kwiecień, 2013 translated by Maciej Świerkocki |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2013 Galeria FF ŁDK i Autorzy |