![[Rozmiar: 12171 bajtów]](../fabjan/fabjan.gif) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Paweł Fabjański’s Play With Capture |

|

1. The Forest For long he believed he was still striding through the forest, in the numbingly warm wind, which seemed to blow from all sides and move the trees like snakes, follow-ing the barely visible blood-trail of the regularly pulsing ground in an always similar twilight, alone in the battle with the animal. (…) When the wind increased, he was lashed by trees and branches more often on the face neck hands. The touch was at first rather pleasant, a caress or as if they were testing, although superficially and without particular interest, the texture of his skin. Then the forest seemed to thicken, the kind of touch changed, the caressing became a measuring. Like at the tailor’s, he thought, when the branch circumscribed his head, then the neck, then the breast, the waist etc., the forest seemed to be interested even in his step, until it had taken his measure from head to toe. The automatic nature of the proceedings irritated him. Who or what directed the movements of these trees, branches or whatever else out there was interested in his hat number collar width shoe size. Could this forest, which resembled no forest he knew, had “walked through”, be named a forest at all.

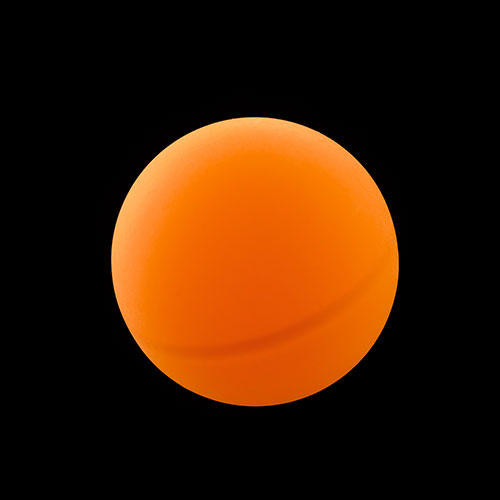

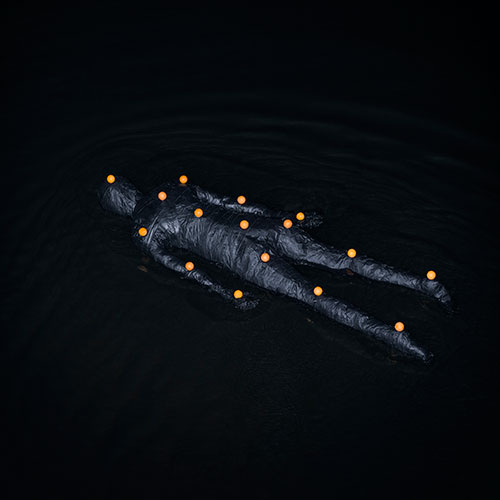

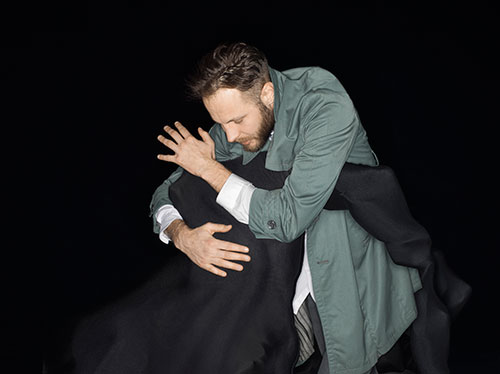

This fragment – a biting critique of the German Democratic Republic’s public institutions – itself an interlude in Zement, a play by Heiner Müller from the 1960s, seems strangely topi-cal. Are we not identified, measured, analized and archived at every turn today? Is there someone there, directing the forest of branches that caress our bodies, predict our move-ments, anticipate our plans, our desires? Where is the threshold between us and the forest? He was still thinking about it, when the forest once more gripped him. The factuali-ty studied his skeleton, the number, strength, arrangement, function of the bones, the linking of the joints. The operation was painful. It was difficult not to scream. He threw himself forwards in a quick spurt out of the embrace. He knew, he’d never run faster. He did not get any further, the forest kept up with the tempo, he remained in its pincers, which locked around him and pressed his entrails together, his bones rubbed against each other, how long could be stand the pressure, and understood, in the rising panic: the forest was the animal, for some time now the forest he thought he was walking through had been the animal, which bore him in the tempo of his steps, the ground-waves were his gasps and the wind his breath, the trail which he followed was his own blood, of which the forest, which was the animal, since when, how much blood does a human being have, took its sample; and that he had always known it, only not by name. The animal that the forest is touches the most secret recesses of our being, beyond the limits of any intensity. Each branch of the forest through which we stride seems to take part in this probing, becoming a sensor that participates in the transforming of our embodied being into a cluster of information streams. At the same time it seems as if we were less. Where is the threshold between us and the forest? 2. Apparatus This moment of caressing, of probing that we are subjected to does have a name – capture. However, it is not a subjective moment, it is no gesture, because there is no-one to perform it. Rather, an impersonal instance is responsible, one that Michel Foucault dubbed apparatus (le dispositif) and that “appears at the intersection of power relations and relations of knowledge.”1 Needless to say, what is at stake here is not simply the question of technology, the fact that we are incessantly recorded and archived by the current apparatuses. Broadening Foucault’s already broad category, Giorgio Agamben defines apparatus as “literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings.”2 According to Agamben one should count not only prisons, hospitals, schools, academic disciplines and factories among apparatuses – as Foucault would have it – but also mobile phones, cigarettes and even language; everything that establishes a discontinuity between the living being and its environment. This discontinuity, this distance, always established anew, also has a name – the subject. A very important thought, because it problematizes the autonomy, the externality of the thus “captured” subject toward the world. And although one could say that we are living in a moment of an unheard-of accumulation of apparatuses, we simply cannot remember the time before them. They are not something that happens to us. The subject is not something given (we are not born as our “selves”), but a constant becoming; an infra-thin interval between the living being and the apparatuses that render the world as such accessible and experienceable; a membrane of sorts that provides the contact surface with other subjects, that is the condition of humanity, and the interpersonal. This is exactly why, for Agamben, the subject is “that which results from the relation and, so to speak, from the relentless fight between living beings and apparatuses.”3 The understanding of subjectivity in terms of struggle also suggests that apparatuses – although inexorable – are not necessarily benign. Indeed, in the condition of extreme capitalism there occurs a radical accumulation and expansion of apparatuses that is accompanied by an intense proliferation of processes of subjectification. That which we were accustomed to call a subject splits into innumerable “images,” “versions,” “aspects”: “I” as mobile phone user, activist, parent, of course, lover of Japanese underground cinema, pork gourmand, tea connoisseur and finally consumer, even-tually consuming my own subjectivity. This is why such a proliferation of processes of subjec-tification ultimately leads to a dispersal “that pushes to the extreme the masquerade that has always accompanied every personal identity,”4 to desubjectification. Thus finding one’s “self” in a forest of apparatuses is not a question of their right use (because we don’t “use” apparatuses), a neither is it a question of struggle – clearing the forest would amount to cut-ting oneself. In the confusion of the tentacles, which could not be distinguished from the rotat-ing knifes and axes, the rotating knives and axes, not from the tentacles, the knives axes tentacles, not from the exploding minefields carpet-bombing neon signs bacterial cultures, knives axes tentacles minefields carpet-bombing, not from his own hands feet teeth in the provisional battle which is named space-time out of blood gelatin flesh, such that the blows against the substance of the self which occasionally occurred, the pain or conversely the sudden increase of in-cessant pain into what was no longer perceptible was his sole barometer, in per-manent annihilation leading always anew back to its smallest components, always assembling anew out of his ruins in permanent reconstruction, sometimes he put himself together wrong, left hand on right arm, hip-bone on upper arm-bone, due to haste or lack of attention or confused by the voices, which sang in his ears, choruses of voices stay in line relax already give up (…) 3. Play Because there is no way to defeat, or even rein in apparatuses, it seems that we found our-selves in a dead end, a moment where we seem to perceive the horizon of the subject as we have known it. Vilém Flusser, in his approach to the contemporary apparatuses and the his-tory of the production of tools by human beings – as devices to distance the world and thus making it accessible – seems to have taken a similar path. He also claims that it is impossible to defeat apparatuses, but he thinks one can play with them; and maybe, from time to time, even play them. For him freedom – and freedom has been the stake of all this all along – is the space that opens up in the play with apparatuses (and is it not so that the interpersonal realizes itself exactly in play?). 5. Paweł Fabjański decided to play. To play (with) the devices of capture, the apparatuses of the forest that keeps studying us. He scrutinizes the machine that the forest is, and through with we believe we are striding, in the instant we feel its caresses. His models’ bod-ies are covered in markers, allowing for the capture of the nature of our gait, our facial ex-pressions, even for the reconstruction of the body as autonomous whole; despite its ab-sence, its death, having descended into nothingness. He shows the futility of confrontation, of the solitary battle with the animal: all bearings disappear, the space melts away, and what remains is the studying, the rubbing of bones against each other, the pain. Pathos also evaporates. What we see is not a heroic fight but tomfoolery, a drunk’s brawl, the iron embrace an attempt at staying afoot rather than at breaking the opponent in two. In any case: where is the threshold between us and the forest? Fabjański’s protagonists do not seem to be in possession of their own bodies – they are either absent ( stay in line relax already give up), blank ( the sudden increase of incessant pain into what was no longer perceptible), or mismatched ( always assembling anew out of his ruins in permanent reconstruction, sometimes he put himself together wrong). Any attempt at identification is void. The distancing effect is reinforced by the markers – in exquisite, saturated orange, they do not disguise their base materiality as ping-pong balls. It is all play. The trajectory of the ball-projectile does not suggest the death of the protagonist, but registers the putting on of a clown’s nose, which returns in the struggle with the apparatuses’ dark matter. The ball even assumes the status of cult object: on the one hand as a death star (in all plenitude of its celluloid self), on the other hand – as a promise of happiness drifting against the backdrop of a pastel gradient, framing Fabjański’s whole project. This promise of happiness seems crucial here. “At the root of each apparatus – Agamben claims – lies an all-too-human desire for happiness. The capture and subjectification of this desire in a separate sphere constitutes the specific power of the apparatus.” 6 This promise also explains the „commercial“ aftertaste of the series, especially its second part, rendered in smooth pastel colours: the girl blows lightly, and the ball floats in space – ad infinitum.

(…) sometimes he delayed his reconstruction, waiting eagerly for total annihila-tion with hope in nothingness, the unending pause, or out of fear of victory, which could only be won by the total annihilation of the animal, which was his residence, except perhaps for the nothingness which waited for him or for no-one; in the white silence, which announced the beginning of the final round, he learned to read the always different building-plan of the machine, which he was stopped being was again different with every glance grasp step, and that he thought changed wrote it with the handwriting of his labors and deaths. 7.

|

Krzysztof Pijarski |

|

1 Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus?, w: idem, What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, Stanford University Press, Stanford 2009, s. 3. 2 Ibidem, s. 14. 3 Ibidem, s. 14. 4 Ibidem, s. 15. 5 Zob. Vilém Flusser, Ins Universum der technischen Bilder, European Photography, Göttingen 1999. 6 Agamben, What is an Apparatus?, s. 17. 7 W tekście wykorzystałem fragment dramatu Zement Heinera Müllera w przekładzie moim i Agaty Lorkowskiej. Zob. H. Müller, Herakles 2 oder die Hydra, w: idem, Werke 2: Die Prosa, Frankfurt am Main, 1999, s. 94–98. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pictures at an exhibitions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright ©2015 Galeria FF ŁDK i Autorzy |