5 - 27 VI 1998

Grzegorz Sztabiński

Photography in the Work of Aleksandra Mańczak.

In the title of Aleksandra Mańczak's exhibition the words "photography", "objects" and "reminiscences" are set in the form of the three sides of an equilateral triangle. Such a structure suggests the equivalence of the three elements. An equilateral triangle may be turned around without changing the value of each element. What used to be its right or left side may become its base, but the nature of the figure as a whole will remain unchanged. I think that the choice of such a structure was not accidental because this way the artist in a subtle and suggestive way points to the ingredients of her idea of art. Their complex relations fill the area of the triangle. Let us examine them from the point of view of photography.

The idea that photography is connected with objects and reminiscences goes back a long way. In fact, ever since the technique of photography came into being and people began to reflect on its meaning, either its objective aspect has been stressed or its ability to form deep relations with the human psyche. Objective approaches to photography have always accentuated the role of the mechanical way of creating images. It has been written that an object actually fixes itself, fixes its own image, on light-sensitive film, and that is why certain factors of individual stylization, inevitable in case of drawings or paintings, have been eliminated from photography. From this point of view a photograph was to be a reliable means of recording and preserving the image of reality. Photography was conceived as an objective ascertainment of the fact of the existence of things, which - as Andre Bazin has written - enables us to take possession of things by means of their image.

At the same time photographs played an important part in people's psychic life. They created a strong feeling of presence of a photographed person, object or place. For this reason photographs were preserved according to a not fully rational realization that they mummify time, stop its flow and allow certain specific moments to survive. In part they also allow to save the existence of photographed people and summon them from the past. As far as this problem is concerned, Edgar Morin stresses the fact that photographs are used in certain magical and parapsychological rites.

The functions mentioned above were often treated as antagonistic. In the history of photography either one or the other concept was supported. Aleksandra Mańczak takes both of them into account. In her approach photography remains in relation both to objects and reminiscences, it is both objective and subjective. These aspects, however, are stressed with variable forcefulness in different series of her works.

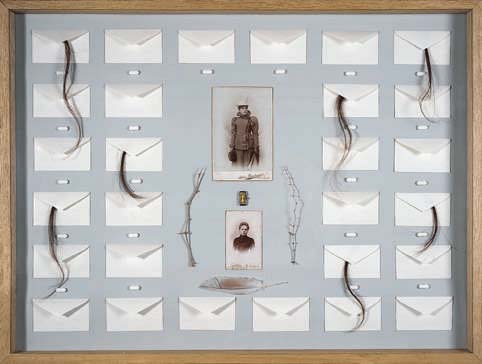

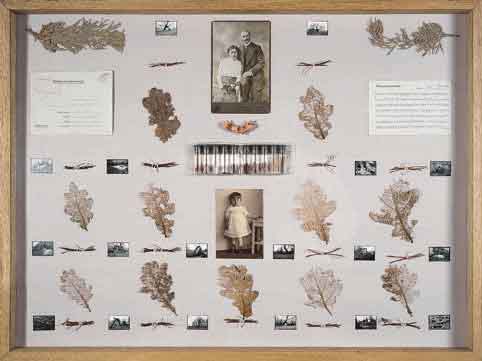

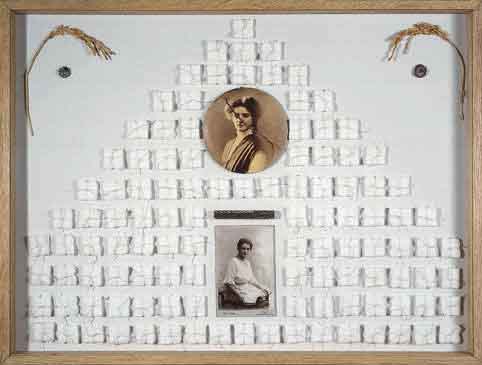

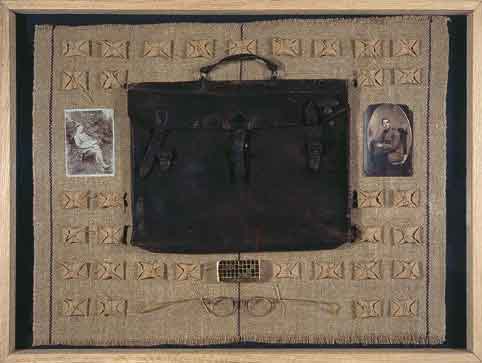

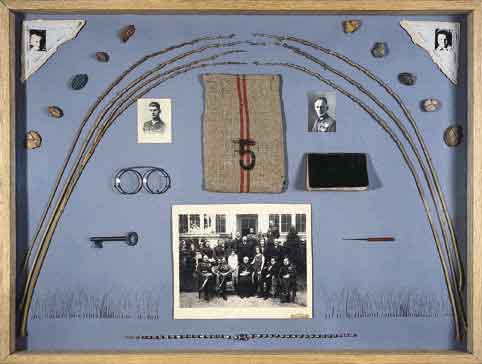

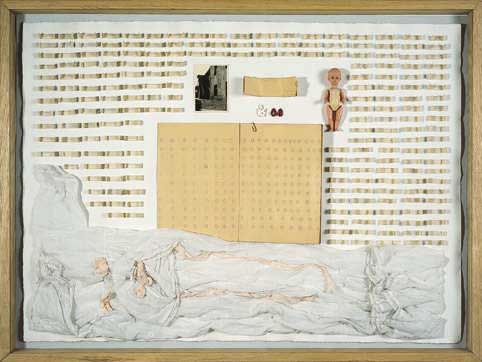

It seems that the subjective approach to photography dominates in the series of collages (or assemblages) "A Very Intimate Sphere - Not For Sale". Using old snapshots Aleksandra Mańczak refers to the past of her own family. She uses only found photographs, taken a long time ago by somebody else. Those photographs are objects discovered in family archives and set against - within the compositional frame - other objects, like her grandfather's briefcase, a pair of glasses, a box of ammunition shells or a letter sent from a concentration camp. Those photographs clearly point to the period of time in which they were taken. Due to their technique and shabby, worn-out appearance, caused by the fact that they had been preserved for many years, looked at and perhaps carried around in wallets, they began to resemble simple, everyday objects. But at the same time they have retained their singularity. Looking at them one may enter their internal world. Thanks to our psychological states and moods the figures in the photographs gain three-dimensionality, they come alive, become present. We look at the faces, trying to penetrate thoughts and feelings of their owners. The eyes of the people in the pictures are turned toward the viewer. The hands, poised subtly and carefully, touch something or hold someone. Aleksandra Mańczak emphasizes her admiration for the mastery of old photographers. Taking a photograph used to be a special occasion, a feast. Photographed people wanted to look their best. Clothes and props had been carefully selected. People's poses were connected with the desire to penetrate and express their characters. These works are surrounded by a very specific aura. The reality evoked opens itself before the viewer and drags him into its own territory. Photography ceases to be an object - it becomes pure reminiscence.

Collections created by Aleksandra Mańczak are journeys through the world of memories. In this context the title of the series becomes clear - in this intimate sphere nothing is for sale. The memories of the artist's father, mother and their parents creates a private reality in which one must behave most respectfully. If so, then why would the artist want to make these contents of her family archives a part of an artwork? Why did she carry them from their seclusion at home to an exhibition, which by nature is a public event? Is she not concerned that those objects and photographs which possess such enormous private value for her will lose their relation with the reminiscences?

It is interesting to talk to the artist in person about her works because one can find out much about specific objects and people in the photographs. For instance a little girl in one of the pictures is the artist's mother as a child. A couple in another picture is her grandmother and her first husband. However, these meanings remain incomprehensible for most viewers. For them those people are simply perfect strangers. If so, perhaps the artist is risking the closure of the meaning of her works and limits the possibility of their deeper understanding to their creators, while leaving the other viewers in the dark. They may not be intruders, but they are certainly unable to grasp the world of relations between objects and photographs presented in successive showcases.

I believe that the situation is more complex. In order to understand it properly it is necessary to distinguish between an intimate sphere of art from a private, personal sphere of memories. Aleksandra Mańczak leads us into her own world of family past and reveals its mysteries for us, but not because she wants us to know them. What she wants is to provoke viewers to remember their own past, to reflect on the past of one's family, to activate our memory archives. Thus the function of this kind of art is not documentary but rather evocative. Its value is not based on the richness, completeness or reliability of sources, but on the power of its influence. What counts most in its effect is the depth and vastness of those layers of memory that will become activated thanks to the series of works entitled "A Very Intimate Sphere - Not For Sale". It is not our mother that is presented in the photographs. The briefcase and the glasses did not belong to our grandfather. But around these objects memories crystallize, memories that otherwise might never have even entered our thoughts.

Aleksandra Mańczak seems to suggest such a process of reception using in some of her works photographs of people unknown also to her. An example may be "Envelopes for an Unknown Woman". In the middle of a showcase photographs of two women are presented. Nothing is known about them. Around the photos there are envelopes and locks of hair. Perhaps the artist is trying to suggest that wisps of hair are often kept as tokens of remembrance of our loved ones, but perhaps what is stressed here is rather the role that hair frequently plays in various magical rituals? All kinds of hypotheses are possible in this case. The past is a sphere of speculation. Reminiscences are equivalent to hypotheses, although there still remain many unexplained secrets. Perhaps this idea, hidden in the works of Aleksandra Mańczak, is suggested by little packets containing some unknown objects. In fact, we shall never get to know the contents of those packets. But on the other hand could we really claim that we discovered the secrets of people and objects presented in the photographs?

The other series of works at the exhibition in question is called "Edges and Peripheries". Their origin is clearly different. Even at first glance one might observe that an objective approach dominates in those works. Aleksandra Mańczak presents photographs she took in Israel, showing, as she herself says, "splinters of civilization". They are fragments of earth covered by damaged and broken objects, a real "waste-bin of the world". These photographic records are shown along with "samples" taken at the scene of the action: earth from wherever the photographs were taken, dried pieces of cacti, a found piece of paper with a fragment of a text written in Hebrew, leaves of grass, bones, a net. Such objects are to verify the authenticity of the photographs, they are proofs. But is only documentation at stake here? Was the artist's only aim to convince the viewer that our planet has been ruined? Why has she chosen motifs from Israel, where Aleksandra Mańczak stayed a few years ago and took part in an exhibition? Numerous examples of the damage done to Nature may be also found in Poland, so perhaps not only objects count here? Perhaps an important part is also played by memories and reminiscences? The place of the works from the "Edges and Peripheries" series cannot be univocally established within the the aforementioned triangle containing the title of the exhibition.

And finally the last part of the show - various photographs taken at different times. We will find among those pictures shop-windows, double portraits where a photographed person co-exists with his/her reflection in the window-pane, strange places where plants grow apparently against the laws of nature, for example between flagstones or on walls of buildings. The artist is intrigued here either by visual effects (lights, shadows and reflections) or by seemingly impossible and absurd phenomena. This is yet another dimension of photography. In this case it exists not as much as an object or a reminiscence but rather as a means of recording, of registering facts. Facts that could be considered impossible if they were not preserved in the photographs. Thus photography becomes evidence. But does this mean that it ceases to be a reminiscence?

Grzegorz Sztabiński

translated by Maciej ¦wierkocki

Copyright ©1998 Galeria FF £DK, Aleksandra Mańczak, Grzegorz Sztabiński