Photographs

14. 11. - 5. 12. 1997.

Boris Mikhailov 's photographic works are stretched between two extreme poles - documentaries and staged photographs, although their relation is not based on simple evolution from documentaries to staging and creation. Sometimes within one work we can find obvious documentary elements, preserved in the photographic image, alongside different, staged elements. Documents and far-fetched creation intertwine, and it should be pointed out here that this does not create any kind of conflict between them. Mikhailov manipulates his photographs, but these manipulations are not directed against the veracity of photography. He does not do it in order to achieve purely visual effects, nor does he wish to deceive the viewer and snare him into his visual traps. His stagings, both those simplest in form, like putting colour onto the picture, and those more complicated, like photo-montage and stagings of whole photographic sets, are used above all as carriers of contents, for Mikhailov 's works are in fact based on their contents. Their anecdote, their literary plot is highly significant and seems to be the main reason for undertaking their creation in the first place. And it is no accident that the author has been working for years on series of works which amplify the literary and narrative aspects of expression. He always returns to the same problems: the past, relation to tradition, the question of individual, personal partaking in history, both recent and long gone, the relation between what is social and what is personal, the sphere of the public and the sphere of the intimate. V sees these problems from a very individual perspective. His art is a mixture of political, historical and personal problems, connected by irony, humour, pastiche and the grotesque. It lets him keep his distance from questions which are often painful and tragic.

The use of document and creativity could be seen in Mikhailov 's photo-montages from the 1960s in which photographic manipulation sharpens the clarity of the image of the surrounding world. In the fragments of a group of photos showing the specific reality of life in the Soviet Union in the 1960s one can clearly see real life as it was there and then. All the esthetic tricks - like photo-montage, the use of slides projected onto the edited pictures and the colours of the polychromatic fragments of photographs - do not weaken their realistic message. Each fragment contains the sometimes sullen truth about the Soviet world. .

Staging in Mikhailov 's art can be seen both in the "organizing" of the photographed object, or whatever is being photographed, in the manipulation of the contents and the interference with the nature of the picture, for example with its colours. In this last instance the procedure is simple - the artist puts a layer of transparent pigment onto a black-and-white photograph. It seems that such a trick might cause damage to the message, distorting the documentary purity of the photograph. In the case of the "U Zemli (Close to the Earth)", 1994, or the "Sumierki (Twilights)", 1993 series, it turns out that the effect is just the opposite. Unnatural colour layed onto a black-and-white photo not only breaks its greyness - both literal and metaphorical, referring to the presented reality - but it also actually enhances the message. In their purely documentary layer the photographs often show the bleak greyness of reality. The added colour is not meant as an ornament of the photograph, it only lets us see its moving contents more clearly. Colour appears in Mikhailov 's photographs not only because black-and-white photography might be thought of as insufficient, but because Mikhailov wants to go beyond convention and emphasise the contents of his pictures. This is also why he uses a special camera to register his world, a camera that can see at a 180 degree angle. Such "half-pictures" make us realise - much more so than standard framing - the limitations of photographic registration and its conventionality. Their panoramic reach marks the beginning and the end of the picture more clearly than a standard photograph. Both the manually laid-on pigment and the uncharacteristic extention of those 180-degree pictures break the conventions of documentary photography. However, the form is still subordinated to the contents which could not have been conveyed by pure black-and-white photography emphatically and universally enough.

The "Sumierki" and the "U zemli" series show everyday reality - in which the author lives - exactly as it is. When the colour was laid onto the surface of developed black-and-white prints, they became monochromatic - blue or sepia coloured. The author used a similar trick in his earlier "Luriki" series (1975-81), composed of manually coloured portraits, bringing to mind the folk and country fair tradition. But the use of colour in his panoramic photographs does not make them any prettier and it does not lead to idealisation. On the contrary, it emphasises the ugly sides of life. Artificial colour adds to these pictures - showing coarse and simple images of various manifestations of life - more drama and pointedness. Both their panoramic format and the filter of colour make them lose all documentary directness and virtuality, characteristic for photography. They carry concrete situations, registered clearly by means of photography, into a somewhat more general and universal dimension, losing none of its contents on the way.

In recent years there has been more and more staging in Mikhailov 's photography, who has moved from presenting and interpreting given reality to creating the object of his interest itself. Mikhailov registers images of fictional scenes that he himself directs. But in spite of such tricks reality surrounding the scenes still penetrates the images, and sometimes it seems to be more "present" in the picture than the fiction staged in front of the camera. Large, staged photographs of parodies of parades in Moscow's Red Square relate to this "here-and-now, hic et nunc" most clearly, perhaps because there is also a political context to them.

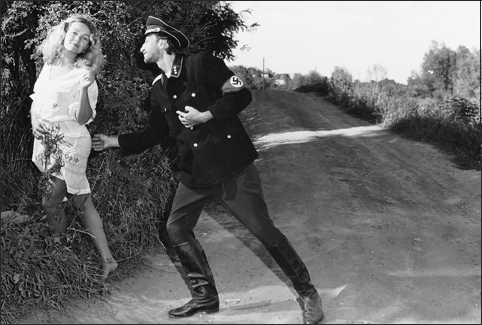

In Mikhailov 's best known series called "If I Were German" (1994) under the naive costume and set of "historical" scenes one can see the here-and-now of life in contemporary Ukraine. The contrast between the real background and theatrical situations deepens the sometimes tragicomical drama of naively artificial and rhetorical gestures of the characters taking part in the scene being staged. And as it happens, historical make-up put on real reality rather reveals than hides the "here-and-now" inherent in the pictures.

This phenomenon does not only concern elements of the real background, but also the author who is one of the actors. What we see is also the projection of his own historical and personal, intimate fantasies. They usually contain some erotic aspects. The situations in the pictures are sometimes coarsely funny, and at other times ironic, while the presented world becomes a burlesque where Eros continually struggles against Thanatos. Coarse humour cannot hide the painful period of history which they evoke - namely the tragedy of the last World War. The historic costume of the actors must be undoubtedly associated with the crimes committed in those years. Some of the characters were victims in real history. Thus under the surface of a historical burlesque we find tragedy, the characters of the victims and their executioners. Relations between them in the photographs are not, however, unequivocal. The erotic sub-context of many a scene reciprocates the relation between the victim and the tormentor as we know it from history. The German oppressor becomes a victim of his own erotic desire. On one of the photographs in the series he clings to the feet of a young Jewish girl, eager to take part in her perverse ablutions. The victim takes revenge on the executioner and, to a certain extent, on history, while Eros triumphs over Thanatos. But Eros's victory is metaphorical and only temporary.

In this series, like in the whole of Mikhailov 's art, he speaks of the human condition, of man's tragic and fatalistic relations with history and tradition. The author shows them bluntly. He speaks of the people and the world he lives in directly and sharply even when the picture is covered by a filter of colour, used only to emphasise expression. Such sharpness and bluntness would be impossible in colour photography, inclined towards the uniformization of our world-view by esthetizing and idealizing everything it shows to an incomparably higher degree than black-and-white photography, which reduces our world-view to a scale of greyness, ranging from white to black..

Mikhailov's art is also rooted in a certain broader tradition of imagery, typical for its native culture. His works have much in common with the poetics of such Russian writers as Gogol and Czechow on the one hand, and Bulghakov on the other. What binds the poetics of Mikhailov 's pictures with literary tradition is their specific relation to reality. It is based on a specific feeling of reality, on establishing strong connections with it, and on incessant references to it, sometimes made directly - as in the series of panoramic pictures - or more metaphorically, using some prosaic, clearly visible elements of real life - as in the series of staged pictures or photo-montages. Reality shown in them - like in the literature of Gogol and Czechow - is presented as it really is, in its manifold manifestations, without idealisation, and sometimes it seems even overstressed with nearly naturalistic bluntness. At other times, like in Mikhailov 's prose, fiction is introduced into the sharply drawn reality. With equally intense attention and often tragicomical ostentation Mikhailov shows what both in men and the world is good and bad, ugly and beautiful, without any attempt at authorial evaluation. The human condition is perceived fatalistically by the artist. The individual is only an element of reality and rarely a subject in relation to it. Man usually becomes an object in a game played by blind and sometimes cruel fate whose verdicts he cannot change. But he may oppose them metaphorically, in his art, taking symbolic revenge on history, as Boris Mikhailov does, violating the documentary conventions of photography and creating fictions within it.

Indeed, it is, one might say, with "postmodern" vigour and carelessness that Mikhailov mixes different orders and conventions, history and contemporaneity, reality and fiction, documents and creation, tragedy and playfulness, truth and fiction. But is what he achieves always worth the trouble? The author often follows a narrow path between an authentic, moving message, and coarse triviality, swerving from time to time beyond the limits of good taste and the limits of distance towards painful and tragic subject matter. But this is the price Mikhailov has to pay for risking an approach that he has been consistently trying to preserve.

In spite of various references to local tradition and local historical experience the art of Boris Mikhailov is well known and respected far beyond the borders of his homeland. It reaches the public both in Western Europe and in the USA, confirming the universality of its message which speaks of an individual dramatically entwined with history and his "here-and-now".

Lech Lechowicz

November 1997

translated by Maciej ¦wierkocki

Copyright ©1997 Galeria FF £DK, Boris Mikhailov, Lech Lechowicz.