|

|

|

From the series 30 Photographs - Karpacz, Polska, 1980 |

|

|

From the series 30 Photographs - New York, New York, 1989 |

|

|

From the series Closed Cemetery - Opole, Poland, 1978 |

|

|

From the series Closed Cemetery - Opole, Poland, 1980 |

|

|

From the series Travel Journal - Jersey City, New Jersey, 2005 |

|

|

From the series Travel Journal - Saban, Quintana Roo, Mexico, 2007 |

|

|

From the series The 1912 Swiss Calendar - Hartford, Connecticut, 1989 |

|

|

From the series The 1912 Swiss Calendar - Wuppertal, Germany, 1989 |

|

|

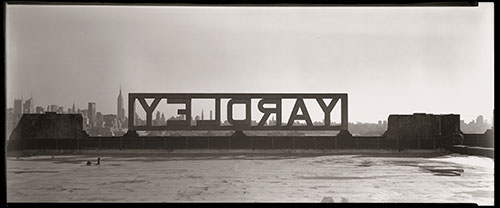

From the series Panoramic Travel Journal - Union City, New Jersey, 2009 |

|

|

From the series Panoramic Travel Journal - Zacalaca, Quintana Roo, Mexico, 2007 |

|

|

From the series Subjective - or the Września Collection, The Family of Chimney Sweepers. Chimney Sweep Company "Florian", Września, 07.05.2010 |

|

|

From the series Subjective - or the Września Collection, Youth Brass Band Września Cultural Centre, Września, 14.05.2010 |

| To Understand the World's Strangeness and Instability with the Eye of a Traveller. Andrzej J. Lech's Pain of Existence. |

Photography hurts. Small sepia morgues.

In bed, on the bus and at MOJE I read Krishnamurtie's Total Freedom. I try [...]

Andrzej Jerzy Lech, fragment of a letter to Roberto Michel

|

|

I. In Socialist Poland. Beginnings of "pure photography" and the quest for the document. 1979-1987.

When the First Secretary’s of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Edward Gierek’s rule came to an end, and when it turned out that Poland was a paper tiger among the economic world powers, i.e. since the end of the 1970s, Andrzej J. Lech, a photographer who lived in Opole at that time and was employed at the local museum, started working professionally and methodically on his first but already important series of photographs, like Cmentarz zamknięty [Closed Cemetery] or W ogrodzie mojej teściowej [In the Garden of My Mother-In-Law]. Between 1981 and 1984 Lech studied in Ostrava at the National Conservatory of Fine Arts and it was there that under the influence of Bořek Sousedik’s lectures he started to think and “see photographically”1. He was also learning on his own, reading “Fotografia” [Photography], a magazine in which the most eminent critics like Urszula Czartoryska and Jerzy Busza, published their texts. The study of Czech and Slovak photographic culture turned out to be very inspiring in Lech’s further evolution as an artist. It was then that Lech also became fascinated for the first time by anonymous studio photography, with its simplicity and no ambitions to be “art”, but sometimes also with a hidden pictorial tradition. We might recall here, too, the initial period of Josef Sudek’s work, which was precisely pictorial. And Sudek strongly influenced the Polish movement of “pure photography” in the 1980s. At the beginning of that decade Lech was also studying the history of American photography which turned out to be the most important for him among all others because it attained its greatest achievements as photography, especially as a document, not as a concept of modernist or avant-garde art, even though it had its modernist accomplishments, too. Polish photography took a completely different turn in the 1980s when the structures of the ZPAF [Union of Polish Art Photographers] and the most important exhibitions of Polish photography exploited precisely the heritage of the neo-avant-garde of the 1980s. It was precisely conceptualism and abstraction from the sphere of minimal art that strongly influenced the phenomenon called “elementary photography” which eclectically combined modern art influences in the formula of medialism with documentary photography that was not regarded as an art form then. Its status was greatly elevated after I Ogólnopolski Przegląd Fotografii Socjologicznej [1st National Review of Sociological Photography] (1980) 2. After a few years of collaboration under the flag of “elementary photography” (1983-1989) photographers such as Andrzej Jerzy Lech, Wojciech Zawadzki, Ryszard Kopczyński, Adam Lesisz, Bogdan Konopka and Jakub Byrczek, personal conflicts broke out between the above artists and Jerzy Olek, the main “manager” of the “elementary” movement. Many artists terminated their collaboration with him while he himself became attracted to the idea of “staged photography”. The efforts of Jerzy Olek, the main animator and artist in the post conceptual tradition, led his concept of elementarism at the end of the 1980s towards a new cultural fashion called “staging”. Beginnings – the quest for one’s self Andrzej Lech’s artistic career began at the end of the 1970s with documentary photography that originated under the influence of his own education and studies in Ostrava. Commentingon this subject, he said: “I respect and value Czech and Slovak photography very much. The Czechs and the Slovakians have probably always been more «photographic»”3 . Between 1978 and 1979 Andrzej Lech produced a very important series entitled Cmentarz zamknięty in which he presented a ruined necropolis and its surroundings, i.e. modernist blocks of flats in the ZWM (Union of Fighting Youth) quarter of Opole4 . The photographer also revealed what was forbidden or at least discussed rather reluctantly – the devastation of many graves, including German ones from before 1945 – which gave his work a metaphorical dimension. Poland in the age of Gierek waged war against religion and its attributes. Especially Jewish and German cemeteries in the Regained Territories were threatened with destruction. That is why this series is a great historical and artistic significance, though we still do not fully realize it5 . Let me add, by the way, that different explorations of the metaphysics of the extraordinary places that graveyards are were undertaken in the 1970s by Mariusz Wieczorkowski and that his works are waiting to be discovered. The exhibition called W ogrodzie mojej teściowej (1978–1984) presents a different kind of seeing – more static and involving a simple motif. In this series we can see how the artist discovered the richness of photographic matter conceived as a mirror of his private life, reduced to the category of a landscape and still life by means of uncomplicated objects and accessories. One of the photographs from this series shows a “sad”, old, white chair against the background of a somewhat surreal wall with a captivating image of a trace of some leaves visible. This work resembles similar photographs by Paul Strand or Walker Evans – modernists from the 1920s and 30s, modernists who wanted to stick to modern, not avant-garde art photography6 . Turning attention to Evans’s approach, unknown in Poland at the time, was very important for the later development of “elementary photography” because the concept of neo-avant-garde art prevailed in Poland for a very long time owing to Zbigniew Dłubak’s attitude, although beginning with his Asymmetry series (1983 to about 2000) Dłubak became much more interested in the exploration of photography and the study of the paradoxes of visual perception, and he continued to explore these problems until the end of his career. The determining of “the being of photography”. Martial Law and Zen. December 13th, 1981 was one of the most tragic days in Polish history after 1945. We shall not find any works of patriotic meaning or works contesting the socialist regime of that time in Lech’s photography from this period. Why? Not everyone is born a warrior, not everyone wants to fight. Lech expressed his experience in a different way and already started thinking about leaving Poland because his primary objective was photography – and photography was in the USA where the most important museums and an art market are. A manifestation of his artistic opposition against “the commies” was the opening of a gallery in his private apartment in Opole, called 5d/3, where eight exhibitions took place. One of his earliest series, entitled Byczyna 1982, was influenced by old urban photography. The atmosphere of this period is reflected, in a way, by deserted, “empty” city space, devoid of people. This was already a concrete strategy of continuing 19th century photography of the likes of Jan Bułhak and other photographers-artisans from all over the world. This tradition is rejected in the works that present shop-windows or ordinary devices such as a street fire-plug, they emphasize other visual qualities connected with the tradition of photographic modernism in which the old must be replaced by the new. This series is soaked in the sadness of the times and in the image of a neglected province. It was not a political manifestation, of course, but an attempt at portraying the atmosphere of those sad, tragic days. The search for “emptiness” and its use is also connected with the idea of the road that leads to a certain spiritual state through the practice of Zen7 . This intentionally nostalgic photography, devoid of people - treated as a document, a concrete memory and a historical place - will return in many works that Lech made in the United States. That is why we can speak of the artist’s individual style. Let me mentionas an example Asbury Park, Monmouth County, New Jersey, 2001. In many of his American photographs Lech seems to be the champion of lonely landscapes (Walt Whitman’s tradition), of provincialism, but also of the collapse of the American myth of power. This artistic problem can become extremely interesting in the future if Lech turn out to be the only photographer who turns his attention such untypical vision of America whose image he had transferred to this country straight from the Polish reality of the 1980s. In his case these images overlap in his concept of memory, which can also be associated with the influence of Buddhism, and reincarnation – permanent elements of his early works, although never treated literally. The most insightful interpreter of the “photogenic photography” scene in the 1990s and in the 21st century is a critic from Wrocław, Andrzej Saj. Among the many features typical for this group of photographers especially the one borrowed by Saj from Edgar Morin’s theory seems to be significant. Saj wrote, “Photogenia (photogenicism) is this unique combination of essential features like shadow, reflection and spectre which let emotional elements, characteristic for the mental image, to be transferred onto an image of a different kind […]”8 . An especially important series made by Lech during the next few years, opening onto new visual problems, turned out to be his Kalendarz szwajcarski, rok 1912 [The 1912 Swiss Calendar]. Photographs copied by means of contact method, full frame from a negative and many other ideas were borrowed from the theory of “elementary photography” of the early 1980s, the theory of which Lech was not only a co-author, but its most important figure, not counting Wojciech Zawadzki – in terms of theoretical background and authorial praxis as such9 . Later these ideas were cultivated by the photographers assembled in the 1990s around Zawadzki and called photographers of the “Jelenia Góra School”. This tradition is still alive today although the “new document”, with its colourfulness and the erasure of borders between staged photography (more important here) and the documentary and reportage tradition, is definitely more popular. In the 1980s and at the beginning of the 21st century Lech’s pictures, taking advantage of the characteristic “vision” of an old camera, consistently determined the artist’s style, including the unique and difficult photographs taken against the light, with reflexes on the lens, for example in the series Kalendarz szwajcarski, rok 1912. This series referred to the aesthetics and most of all, the magic of old photography, while his next exhibitions were more modernist: the series 60 furtek [60 Gates] in the typology of Bernd and Hilla Becher came closer to unorthodox conceptualism10 , also in terms of the way of registration. During his stay in Germany (1987–1989) Lech’s approach became somewhat more modern, opening onto the problems of the modern city, including its multinationality, not to be found in Poland at the time. 30 fotografii [30 Photographs] from 1985 should be treated as a manifestation of the affirmation of life. Frames in this series exhibit the most modern style, analogous to German visualism and the tradition of “new photography” from the 1920s and 30s. Karpacz, Opole, and then New York City flicker in fragmentary vision at the moment when the reflection of the world and its reality is concealed by a form of illusion or delusion, like a flowing curtain or strong light. Lech preferred works with a powerful contrast of the chiaroscuro, in spite of the fact that such pictures are risky. We can also see a crumb of concrete memories, like the Jewish cemetery in Prague or ever-stronger examples of consumer culture in the form of posters, which start to compete with real life. In the 1980s and 90s the most often commented series by Lech was Amsterdam, Warka, Kazanłyk…, but more because of its inherent theoretical concept than the problem of visualism that was closer to 30 fotografii. In this series Lech turned his attention to the question, which interested him earlier, namely that images exist independently of the time and place where they were taken. The artist stressed this in a short text in the catalogue of the exposition Zmiana warty. Młoda fotografia polska [The Changing of the Guards. Young Polish Photography] (Galeria FF, Łódź 1991)11 . Andrzej Saj in his article entitled Obrazy widmowej rzeczywistości [Images of Spectral Reality]accentuated, among other things, the specific aesthetics of works by Lech, which he named “the aesthetics of reducing” and placed in opposition to reportage photography or artistic photography of those times from the circles of the ZPAF. Andrzej Lech’s innovation was based on the contact method used to transfer the mental idea of the photograph without losing any fragments of the transmitted image. However, we should mention that he was especially interested in the preservation of integrity and all links with the negative without the possibility of its manipulation, because it was also connected with the quest for the ontology and the truth of the image – which confirms that Lech’s concept was to be first and foremost a document in the sense suggested by Eugene Atget and August Sander in the first quarter of the 20th century, and later developed by Arthur Siegel (Fifty Years of Documentary, 1951), or in another visual sense by Edward Weston (Seeing Photographically, 1943). This was, of course, the American way that marked the rise of the aesthetics known also from the German visualism and Polish elementarism of the 1980s. II. Period of Emigration. Germany, United States (Jersey City near New York, and New York City) At this time, initially only in Jerzy Busza’s “Obscura”, the correspondence between the author and his alter ego, Roberto Michel, was published. Letters to and from Roberto are no ordinary correspondence, of course, but a concrete, descriptive literary form which – and that is more important – they self-reflexively interpret. They are stylistically the same. We can speak here of a poetic atmosphere of subtle melancholy, of sensitivity to the surrounding reality and of a certain mannerism of vocabulary, which I value myself, although I have met with a different public reaction as to the literary merit of these letters, for example during a discussion at a symposium entitled Fotografii czas przeszły i teraźniejszy [The Past and Present of Photography] (Legnica, 1991). Undoubtedly there is a strong connection between Lech’s poetic self-commentary, which those letters actually are, and his photographs. Unspecified places where the pictures are taken and the mysterious figure of Michel combine into one, create more universal problem. The artist’s literary fascination, in my opinion, very interesting and already evident in his photographs, appeared in a different kind of art and awaits penetrating analysis. Lech’s American photographs mark the return to the search for the strangeness and uniqueness of the world “simple in its material substance” and specific archaism. Especially interesting are various places at the cemetery in Jersey City, including a tombstone that has been haunting Lech for years, bearing the inscription MOJE, as well as the often-photographed view of Lower Manhattan whose photographs from before September 11th, 2001, gained new value12 . In 1999 Jerzy Lewczyński’s Anthology of Polish Photography 1839–1989 was published, the only such anthology so far. It presents artists from the circles of “elementary photography”, including works by Andrzej Lech. It was the final gesture of appreciation for his photography. The most important series by Lech in the 21st century is his Dziennik podróżny [Travel Journal], started back in the 1990s. The artist assumes the role of a romantic wanderer, a raveling photographer who remembers the 9th century tradition – thus the question of “eternal return”, borrowed from the theory of reincarnation, appears yet again in a different form. The artist like an invisible phantom records all the places he visits. He registers his ephemeral trace13 . Why does he wish to return to a non-artistic concept of artisan photography? Because he believes that the most important photographic achievements have been made in the 19th century. Lech is interested in “empty” spaces. It is easy to see Atget’s influence in those pictures where Lech turns his attention to desolate and forgotten places. However, Lech resembles a painter more than his great French predecessor and he is even specifically pictorial14 . He makes his prints unique by toning them and in tea. Krzysztof Rytka interpreted those works in the following way: “And now these photos by Andrzej. I have seen many of them and even if they show many different places, lying hundreds of kilometers apart and in different parts of the globe, I cannot help feeling that they all have something in common. I do not even try to define this integrity, it is too difficult a task; however, I can grasp this «something» unconsciously and it is something surprisingly familiar. […] These photos are not memories of places, which Andrzej visited during his journey through life. It is a specific kind of documentation of his confrontation with them, but not the kind that characterizes the documentation of reporters. This is because it is his own settling of accounts with his own memory which includes moments from the lives of people who are no more and whose stories have been stripped precisely of illustrations which we could loot at while listening to them”15 . It is worth noting that Andrzej Lech is also a collector of old photographs and old photographic equipment. Some of the photographs from his collection, for example by Eadweard Muybridge, and unique photographic cameras, seem to be a part of a programme analogous to the “archeology of photography” by Jerzy Lewczyński, which is also confirmed by Lech’s correspondence with Roberto Michel devoted to the above-mentioned photograph by Eadweard Muybridge16 . In his Dziennik podróżny the artist presented ordinary places but at the same time he changed them into oneiric, unreal objects, so that his journey would seem endless, without beginning and aim, which conceptually referred to his series from the 80s: Kalendarz szwajcarski, rok 1912, and Amsterdam, Warka, Kazanłyk... To this end Lech employed his style from the 1980s, based on the use of full frames and specific aesthetics, even though in the series in question he included works of panoramic format which started coming into being as early as 1996. How can we sum up the state and character of Dziennik podróżny today? Let me quote again an insightful commentator of Andrzej Lech’s work, his childhood friend from Wrocław, an archeologist and poet living in Germany, Krzysztof Rytka: “The images that Andrzej registers are a documentation of a journey in time. […] It is perhaps the moment when such a journey is still possible. Because if we carefully look at the curtain which covers those photographs, we can see life throbbing in them. Of course, we need imagination to see it, but is it so difficult? Try to tell the story of one of those pictures, reaching into the treasury of your own «personal» pinakothek. When I look at those images I realize, God knows which time again, how helpless the attempts at describing similar experiences in words are”17 . III. Beauty and melancholy. “Photography is life”. Panoramiczny dziennik podróżny [Panoramic Travel Journal]was supposed to be shown in 2010 but the exhibition planned in Galeria Pusta did not take place after all. Photographs of a large and rare format, 7 x 17 inches (about 18 x 43 cm) were copied by contact method. These works refer to a more natural kind of visual perception than formats based on the rule of the so-called “golden division”. Visually it is a continuation of Dziennik podróżny. An empty beach or the loneliness of an artificial palm – here is nostalgia in which artificiality becomes, or only pretends to be, natural. Modernist bridges from the beginning of the 20th century or a ruined church in Mexico (Suban, Quintana Rao, Mexico 2007) are other themes of the series. The impression of loneliness and further quest by eternal travelling is intensified here. In this way the artist returns to the concept of photography from the second half of the 19th century, to the photography, which tried to find a new or even modern vision, or way of seeing. In Lech’s case this quest ended with the notion of “photogenia” and later led to a radicalized modernism in the form of the classic avant-garde18 . Commissioned by the mayor of the city of Września in 2010, Lech using a panoramic camera took pictures of the inhabitants of the city (his work was a part of an artistic project called Wrzesińska Kolekcja Fotografii [Września Photographic Collection]). The result was a sociologically broad compilation of group portraits of people from small town community. At the same time this monumental project is an attempt at recalling “posed portrait” photography, typical for “artisan” photography of the 19th, but also the first half of the 20th century. In this series we can certainly also see some similarities to the concept of typological photography by August Sander as well as to portrait photography in the mode of Zofia Rydet. But in Lech’s case we have to do with yet another message. Photography not only preserves, but also prolongs simple life in its ordinariness, though without the hustle and bustle of everyday routine. Lech’s photography is “simple” precisely in those terms. Some critics, like Wojciech Zawadzki, understand it instinctively, while others, like Andrzej Saj, John Wood19 or myself have been interpreting it for years with admiration. Let us return for a moment to the question of photography by Andrzej Lech and pictorialism. I agree with the artist himself who wrote in his e-mail to me: “You know, I think we are all contemporary pictorialists in a way. True, we do not use gum printing, bromoil and so on, but above all we think of the image… The image is our goal. Ewa, Wojtek, even Kuba, Bogdan and many others… Naturally it is not the same pictorialism the artists of that period talked and wrote about, and most of all, practiced…”20 . I believe that the responsibility of a true artist is a quest conducted within the given category of art, which means being true to the photographed reality that is a reflection of concrete existence. Pictorialists intentionally simplified the image of the world; they wanted to see it only as beautiful. In the works of such Polish photographers like Lech, Andrzejewska and Konopka, the world’s image and expression is more ambiguous, based on the notions of documentarism, visuality and nostalgic beauty. Mundus melancholicus in Lech’s concept21 So what is Andrzej Jerzy Lech’s photography like, counting from the end of the 1970s to the present day? The measure of its meaning and characteristic features will also be determined by those photographers who will take a similar creative road or reach it on their own starting from analogous assumptions based on a theoretical postulation that photography is an optical and chemical form of registration, not an electronic one – because the registered image has a completely different aesthetic, and therefore, also philosophical expression. But more important is the emphasis on concrete poetic imagination, in which time and place, as it has often been stressed, disappear. Under the influence of Zen. Equally important were old cameras that Lech started using in the 1980s and a pin-hole camera he took to in the 90s, which gave his works a specific aesthetic quality, connected with a hard-to-predict deformation of the image. In this respect the series Kalendarz szwajcarski, rok 1912 stands out, due to its untypical format (6 x 9 cm) and the so-called “aesthetics of an error”, based on the registration of light that falls into the lens and ripped off bellow. It is important that in this instance the artist refers to the concept of reflection of reality conceived as mimesis. Is it an obsolete formula? It is certainly not very popular nowadays because photography has always been a technical kind of art treated as entertainment, only seldom as culture, and only exceptionally as art. Lech’s aspirations are artistic and I believe that many of his works and their theoretical concepts will secure a place for themselves in the history of Polish and world photography. I especially have in mind such series as Cmentarz zamknięty, Amsterdam, Warka, Kazanłyk... 30 fotografii i Kalendarz szwajcarski, rok 1912. All the above-mentioned series are characterized a melancholy approach to the world, which is not considered as a stable and godly phenomenon but as something in the state of permanent disintegration that is not violent, however, but gradual, and in this case, hidden. Lech’s only salvation in this world is photography, but even photography hurts. Constantly and until the end… |

Krzysztof Jurecki |

|

1 See K. Jurecki, Andrzej J. Lech, [in:] Wokół dekady, Fotografia polska lat 90. [Around the Decade, Polish Photography of the 1990s], Muzeum Sztuki [Museum of Art], Łódź 2002 (catalogue of the exhibition).

2 See K. Jurecki, Fotografia polska lat 80. [Polish Photography of the 1980s], Łódź 1989. 3 A.J. Lech [a statement], in conversation with K. Jurecki, [in:] K. Jurecki, K. Makowski, Słowo o fotografii [A Word on Photography], Łódź 2003, p. 133. 4 On the origins of his photography and his own idea of it see K. Jurecki’s interview with Andrzej J. Lech [in:] K. Jurecki and K. Makowski, A Word on Photography, op. cit., where Lech said, for example: „Photography is my life. After so many years of photographing, photography is I. I don’t exist without it. It’s a confession, an act, protection, memory, nostalgia, and a narrative of myself. It’s my passion. […] I’m happy that I can see” (p. 138). 5 The series was shown only once in 1981 in Opole not counting a little note in „Fotografia” and has not been properly analyzed yet. 6 In Poland, not counting Janusz M. Brzeski, actually there were no modernist photographers aware of its wide-ranging potential. There was a clear and uncompromising division into „artistic” (pictorial) photography and the avant-garde grouped around Władysław Strzemiński. For these reasons I interpret Lech’s 60 furtek as postconceptual images in the tradition of mining head frames and other typological works by Bernd and Hilla Becher, and to a decidedly smaller degree as a documentary project because conventionality and repetition are most important in it, not the search for unique and specific features that could be also found here. 7 A. Lech, letter to K. Jurecki, Wuppertal, 23.02.1988, and A. Lech, Jak zastosować formułę koanu w sztuce polskiej? [How to Use the Koan Formula in Polish Art?], [in:] Koany w Elektrowni. Dzieło sztuki jako koan [Koans in an Electric Plant. An Artwork as Koan], Mazowieckie Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej „Elektrownia” [Mazovian Centre For Contemporary Art. „Electric Plant”] in Radom, 2009, pp. 153–167, (catalogue of the exhibition). 8 A. Saj, W kręgu twórczości fotogenicznej [In the Circles of Photogenic Art], „Format” 1992, vol. 3–4, p. 85. A. Saj, Elementaryzm a wizualizm w fotografii [Elementarism versus Visualism in Photography], [in:] Materiały. Sympozjum XXI Konfrontacji Fotograficznych [Materials from the Symposium of the 21st Photographic Confrontations],Gorzów Wlkp. 1991. The most important summary of the achievements of „photogenic photography” and a formally different group of artists from PAcamera in Suwałki was the exposition called Bliżej fotografii [Closer to Photography], (BWA, Jelenia Góra [1996]), which was the height of the evolution of this type of photography in Poland. At the beginning of the 21st century a group of „new documentarists” appeared which combined a few tendencies: document, commercial (advertisement) and staged photography, treated as a new formula for a document. The man behind this new but eclectic phenomenon was Adam Mazur. We should also add that A. Saj as a photographic critic and editor-in-chief of „Fotografia” did quite a lot for the popularization of „elementarism” and the „Jelenia Góra school”, as this tradition is called. Names are not important, rather what hides behind them, what idea and form. 9 I wrote about it [in:] Polish Photography of the 1980s, Łódź 1989, in the chapter Fotografia elementarna [Elementary Photography]; K. Jurecki, Andrzej J. Lech, [in:] Around the Decade. Polish Photography of the 1990s., op. cit. 10 The idea of magic often reappeared in the discussion on Polish photography of the 1980s and 90s, not only in the context of pictures by Lewczyński or Rydet but also „elementary photography”. Behind the inaccurate term „photographic magic” we will find the theory of Roland Barthes, Edgar Morin and Andre Bazin, popular among Polish artists in the 1960s and 70s, bearing in mind that Barthes had been known until 1980 as the author of La chambre claire: Note sur la photographie (published in Poland as Światło obrazu), and as a structuralist from his Mythologies, (published by Seuil, Paris 1957). 11 U. Czartoryska pointed this out, too, in Time Intensified. Ten Photographers on Their Path of Time. Polish Perceptions. Ten Contemporary Photographers 1977–88, Collins Gallery, Glasgow 1988, pp. 11 and 12, (catalogue of the exhibition). One should add that it was one of the most prestigious exhibitions of the 1980s. Lech also took part in important wide-ranging group exhibitions the last one of which was XX wiek fotografii polskiej. Z kolekcji Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi [20th Century of Polish Photography. From the Collection of the Museum of Art in Lódź], The Shoto Museum of Art, Tokyo and Niigata Art City Museum, Niigata, 2006. We should add that there are 40 works by Lech at the Museum of Art in Łódź, the last of which were acquired in 2002, and it is a pity that they have never been presented at a permanent exposition. 12 I would like to stress that some night photos from 1994 taken in Jersey City resemble Bogdan Konopka’s works, who had been already working in France on his own style, which began to take shape in the first half of the 1990s. Paradoxically their photography is most similar of all since it focuses on desolate, forgotten places or places destined for destruction, though Lech’s concept is more varied stylistically – from the inspiration of studio photography of the 19th century to the effects that bring surrealism to mind. Konopka remains faithful to one kind of aesthetics characterized by „grayness”, but he sometimes tries his hand at portrait photography, too. 13 I am referring to my text called Dziennik podróżny [Travel Journal], “Exit” 2006, vol. 4. 14 I interpret pictorialism as a permanently present form of artistic photography that naturally has its pros and cons. Lech is decidedly closer to „pure photography” but some of his aesthetic ideas are closer to aesthetics in the philosophical sense, not to the theory of pictorialism. The documentary value in Lech’s photographic series was analyzed by Z. Tomaszczuk in: Z. Tomaszczuk, Z punktu widzenia obserwatora dokumentalnej sceny fotograficznej w Polsce [From the Point of View of the Observer of the Documentary Photographic Scene in Poland], www.profotografia.pl/o-fotografii/13-tomaszczuk (accessible since 10.12.2010). 15 K. Rytka, [untitled], Dziennik podróżny; Warsaw 2006,Yours Gallery, (catalogue of the exhibition), pages unnumbered. 16 A. Lech’s letter to R. Michel, New York. Saturday, November 25th, 1996: Dear Roberto,We should add, by the way, that this literary form of writing about photography and the style of Lech/ Michel Mariusz Wieczorkowski compared to Blaise Cendrars’s during a discussion on Polish photography in Legnica in 1991. In my opinion such a literary form is very interesting in the context of photography and at least completes, if not colours it, in the positive meaning of the word. 17 K. Rytka, op. cit. 18 See L. Delluc, Fotogenia (fragmenty) [Photogenia (fragments)],[in:] Europejskie manifesty kina. Antologia [European Cinematic Manifestos. An Anthology], selected, introduced and edited by A. Gwóźdź, Warsaw 2002. The text gives also another meaning of „photogenia”, namely the “prettiness” of a film image, which Delluc opposed in his article from 1920. 19 See J. Wood’s text in this catalogue. 20 A. Lech, e-mail to K. Jurecki, 10.01.2011. 21 W. Bałus, Mundus melancholicus, Cracow 1996. |

| Listy przez Atlantyk |

|

Roberto Michel, a translator living in Paris – is he Andrzej J. Lech’s alter ego or a real person? An exchange of letters that has been going on for over twenty years now, a beautiful friendship: so many seemingly banal but actually meaningful personal confessions – an exceptional understanding above words… In spite of the fact that there have been long breaks in this correspondence, periods of silence. Perhaps they hide what is not meant for publication? A Polish photographer from New York, who sometimes published some of those letters in the catalogues of his exhibitions, reveals that altogether hundreds of them have been written since both addressees met, i.e. since 1989. So we know only selected letters – those which happen to be an interesting commentary to Lech’s photographs, that are its “other side”, something like a description on the back of a picture.

“Photography. Photographers know nothing. Theirs is a blissful, happy, safe state of ignorance. Great. Photographers are supposed to be stupid. Poets can also be stupid, if they can. Do you know Heiner Müller’s The Rotting Shore, Hamlet’s Machine, Love Story? Fear of women. And I am afraid of photography, and probably always have been. But most of all I am afraid of those old photographs. They are all a paroxysm of pain. Benjamin and his theory of aura. The continuity of photography. It’s been so many, so many years of light. Please look at the painful Isabelle by Francesco Paolo Michetti. 1878. Sepia toned prosectoriums. I hate these beautiful photographs…” This is Roberto writing to Andrzej, on Thursday, March 19th,1989. So the ground for their understanding across the Atlantic is perfectly clear: it is the mutual fascination with photography. A fascination which is not only enormous, but also too strong; so strong that it hurts. Andrzej J. Lech collects old photographs. He finds in them what is nearly absent in contemporary photography: enchantment with a mere fact of taking a picture of the vision of reality; a picture that does not disappear like a mirror reflection, but remains, unmoved, unchangeable. His own photographs refer stylistically to the early, still 19th century photography which at the time was treated deadly serious. It had nothing to do with playing with pictures, but much to do with death, in fact it played a part of “a death-mask”, as Susan Sontag wrote. For this tireless voyeur, who has been adding new pictures to his Travel Journal for years, each of them is an epitaph for this unique fragment of the space-time continuum that is gone forever and is (though in a moment – was) our personal property. In a letter written in New York on Saturday, November 25th, 1996, he tells the story of a certain valuable trophy in his collection: “A few years ago I bought this unusual and very interesting stereophotograph from a New York collector. It was taken by Eadweard J. Muybridge in San Francisco not long before 1869. In the centre of a group of seven men, carefully „placed” on the left, we see Muybridge himself, who often appeared in his photographs. Sailing boats in the harbour look as if they were also specially set for this well «balanced» «photographic composition»”. Photography as an image, and therefore, most of all, as an unmistakable composition that provides the meaning of the whole frame to its every fragment. An image in the full seriousness of the word – that is what Andrzej J. Lech is looking for in the pictures he makes, as he stresses writing about Muybridge. An orthodox concept of the image that he has been consistently holding on to contains its elementary features, both these which it inherited from painting and those that are the result of photography’s own specificity. The use of the traditional negative with its “touch of light”, classic composition, typical perspective of the human eyesight, the masterly use of light and shade (black and white) and the documentary illusion of the direct view with the attempt to register the largest number of details possible – all these elements of the authorial conception make up an archetype of the photographic image. The photographer refers precisely to this archetype, programmatically continuing with his works the tradition of “the first photography” when light sensitive image was still an almost magical phenomenon demanding to be discovered and discovered anew. A phenomenon whose initiation was celebrated every time. Other people’s pictures, treated as carefully as his own, sometimes change places with them. “[…] I am sending you three photographs that have exceptionally moved my imagination, and most of all, the memory of the past” – writes Andrzej to Roberto on Tuesday, August 23rd,1993. Aura of mystery and the paralyzing “suspension” of time… These pictures have been taken around 1954 by an anonymous American portrait and landscape photographer. They come from a larger series described by the photographer modestly and laconically as The New York Bay View Cemetery, 1947 – 1954. Jersey City, New Jersey. In memory of MOJE. Love, K.H.” The disturbing and intriguing inscription “MOJE”, chiselled in the tombstone, became a pretext for a whole imaginary story of those found photographs. This old cemetery, lying near his house, a cemetery Andrzej J. Lech persistently photographs, probably looked the same forty years earlier. In this special place the overlapping layers of time are transparent: a picture taken there does not embrace any definite time; a slight manipulation (longer exposition time, sepia) suffices and it is impossible to determine when it was exactly taken. Sometimes it is not the place but the moment which becomes so special that it is able to contain two different places simultaneously. The photographer from New York sends his friend from Paris a photograph of a man in the window. “The fog here today is enormous – he writes. I open the window and see Little Pond. I don’t know where the Empire State Building has got to. I also can’t see the Hudson River which I cross by ferry twice a day. The Karkonosze Mountains, Samotnia and room number 17” (Jersey City, New Jersey, Thursday, June 15th,2000). Is this a photograph of the author in Samotnia or in New Jersey? The fog outside – is it Polish or American? For Andrzej Jerzy Lech it is simultaneously one and the other place. A photograph at this moment is for him most of all a document of personal experience, an intense nostalgia for the moment that passed. A document of memory. The overlapping of different places that meet in one photograph also occurs in the case of the twin pictures that Andrzej presents to Roberto in a letter written in New York on June 17th,1991: one of them is signed “Karkonosze, Little Pond, 1932”, the other – “Enchantment Basin, Nada Lake, 1991”. An image seen on the focussing screen of the camera evokes this second image, hidden in memory… These mystifications, employed by the author as a meaningful strategy, become an important statement on the ethos of photography as a document. Andrzej J. Lech shows us and lets us see with our own eyes that photography often gains true meaning when it is a subjective document of personal memory, and then it becomes less important as an account of the objective state of affairs. The close and inseparable connection of photography with ordinary private life – with the savouring of the immersion of one’s own person in this and not any other place and time, the place and time that overlies other remembered moments and places in our imagination – this is a lasting feeling that appears directly in the letters of Andrzej to Roberto and of Roberto to Andrzej. And in the evening in a dark darkroom, listening to Davis and Baker, to Cash and Nelson, I develop my further «mysteries». The light is red and I’m drinking red wine from Chianti, in solitude, which I also like. The alchemy of photography has many forms. This is one of them…” (Jersey City, New Jersey, June 11th, 2005). The act of photographing and then “alchemical” work in the darkroom is a form of the conscious living of one’s own life; this form is most intense for somebody who treats the taking of the picture as a spontaneous reaction to perceiving something important. It is also a way of his contemplation, or even meditation in the spirit of Buddhism Zen. “In religion the future is behind us. In art the present is eternity…” It is not without reason that Andrzej J. Lech has picked this quote from The Book of Tea by Okakuro Kakuzo as the motto for his art. “Listen! Everything that’s important for you and your camera takes place merely five metres away. I already know this. What about you?” – asks Roberto on Thursday, March 19th,1989. Did this revelation have to cross the Atlantic in order to reach the photographer, or is it perhaps an important element of his self-knowledge for him, establishing the foundations of a completely conscious and openly proclaimed programme? Between these letters not only the space of the ocean, but also of time opens up. In the course of over twenty years of this correspondence the author’s personality was changing, which can be clearly seen both in the subject matter and form of the letters. The early confessions are often a record of a whirling stream of consciousness: full of chaotic, overlapping observations, filled with often violent emotions. The literary form expresses this state of exhilaration by means of subjects and objects multiplied in a sentence: words are enumerated after a comma one after the other as if uttered in one breath. In this fast course of a nervous narrative we can feel the confrontation of one’s own person with the external world whose noise floods and overwhelms us. It is hard not to feel that way for a reflexive photographer, violently thrown from the world of Polish stagnation of the 1980s into the very centre of New York’s excess and crazy pace of life. “And most of all mad New York City. […] I photograph this jumble every day. Blue Brother Coltrane, sweet smell of cinnamon, yellow taxis, beautiful whores, baked chestnuts, Central Park, Fifth Avenue, an immigrant, Igor (a graphic artist from Kiev), fantastic street musicians, the subway, the quiet and charming Greenwich Village (which sometimes resembles Montmartre), the green Statue of Liberty, high World Trade Center and old Canal Street, little galleries of SoHo and Tribeca. The city of Satan and angels, best artists and black thieves, Jews, faggots, the homeless and Hindus selling newspapers. Here good and bad, greatest wealth and greatest poverty, debauchery, kitsch and beauty are close to each other, they are one” (New York, early spring 1990). How different are the letters from most recent years! Short and focused on one subject. Sentences reduced to the most simple statements, hitting precisely the core, the very centre of the thoughts behind them. In these texts, unlike in the old ones, intensely thickened, there is a lot of free breath, air. And more and more memories, nostalgia. On August 1st, 2004 Andrzej J. Lech writes: “This picture is history. This beautiful chimney was torn down brick by brick, without any respect for the past. […] Passing worries me. I slowly acclimatize, get accustomed to, get attached to. I «deacclimatize», disaccustom and disattach even more slowly.” Photography for this passionate voyeur has always been a window and a mirror at the same time: a self-portrait has been laid over the world, it has been its “other side”. Travelling through the world was simultaneously also becoming a journey into himself. That is how it is also with the literary character of the Travel Journal, made up of his letters to a friend. In time this self-portrait seems even more present in the view of the world – although, paradoxically, it is not as conspicuous. Like light, thanks to which images come into being, it is suspended inside them and permeates them. |

Elżbieta Łubowicz, Wrocław, December 2010 - February 2011 |

More texts: Catalogue of exhibition (fragment, "pdf" 1.28 MB)

|

|

Copyright ©2011 Galeria FF ŁDK and Authors |